Remembered, Reclaimed

Eric Yip on three collections that shed light on overlooked and misunderstood figures of history and literature

Eric Yip

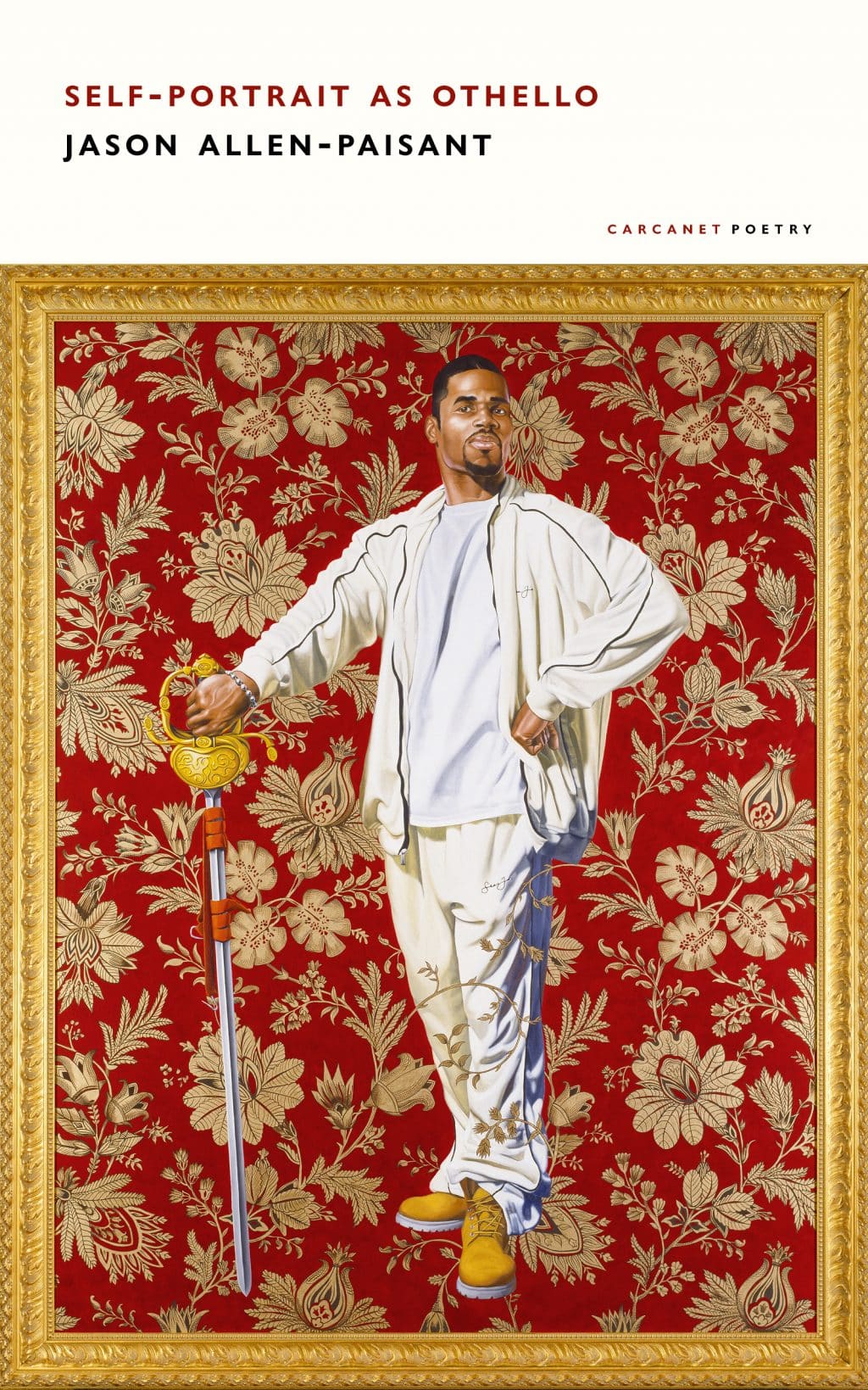

Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello begins with a hesitation towards the titular comparison: ‘How could I resurrect you to speak, / when your burial is in no ground / that I can pilgrimage to’ (‘Ringing Othello’). Yet, the character of Othello seems an apt container for the poet’s reasoning; both the speaker and Othello have in their own stories experienced ostracisation, migration, and the antagonisation of Black masculinity. Allen-Paisant’s achievement, however, is not in simply modernising Shakespeare’s narrative; it is his addition of ambiguity, interiority, texture, and flesh that imbues the collection with an intellectual and emotional energy.

The book’s first section is a narrative sequence that takes us from the speaker’s Jamaican childhood to his studies in Paris and beyond. At first, Allen-Paisant’s speakers are manoeuvring their way through absence and alienation.

Firstly, in Jamaica:

my heart races every time a car

blows horn or pulls up, thinking

that must be my father a him that

come look fi me yes him come.

(‘[I am five. I sit on the barbecue*]’)

Then in Paris where the speaker goes to an opera ‘to act bourgeois’ only to be put down by racial codes surrounding class and culture: ‘come on bredren my Jamaican brother says to me / black people don’t go opera you know this’ (‘[I’m going to Paris at last]’). As the speaker finds himself in a European country where he feels ‘how sharply loneliness cuts the body’, punctuation is phased out, as if to mark a loss of order and confidence. Here, Othello is unmentioned, yet we get the sense of the speaker being in a performance. The character becomes a subconscious frame within which the speaker’s experiences are restaged.

As the sequence progresses, we get the sense that the speaker is not referring purely to the absence of a biological father, but also to how slavery has splintered and dispersed his ancestral line: ‘I call you daddy bois d’ébène / pieces of scattered wood’, and later, ‘Un-Dad Un-Dad I ain’t died I split divide / & recreate I ain’t one I multiplied’ (‘[A horse was neighing]’). This undoing is put into lucid focus in ‘Door of No Return’, the book’s closing sequence named after the exit points from which enslaved people from Africa were sailed across the Atlantic. Allen-Paisant draws several ideas from Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, which posits the Door as a rupture in intergenerational memory.

This rupture is why Allen-Paisant’s speakers are so historically minded, why they are always reflecting on what their spatial and temporal presence implies:

I am dancing

through Europe actor and spectator in a

carnival of bodies.

A doing road in Venice, where the black

Moor head is placed

on doors and wrung by hand every day.

(‘[I sit on the barbecue when

the bath water pour]’)

Yet, Allen-Paisant finds jubilance in this modern possibility. The speakers ‘glide’, ‘dance’, and ‘rise’, mixing Patois, French, and other European languages with ease and glee. The erotic becomes a means through which the Black body’s agency is returned to the self: ‘we hunted carnal pleasure my friend and I / I agreed it was a game of healing and transgression’ (‘[In Prague a hot summer’s day on the Charles Bridge]’).

For Allen-Paisant, biography in both its real and imagined forms bridges the temporal gap Brand describes. The book’s central section contains several persona poems written from Othello’s perspective, occasionally punctured by essayistic prose fragments. Allen-Paisant purposefully blurs the autobiographical, historical, and ekphrastic. Poems alternate between the first person and second person, confounding Shakespeare’s characters like Iago with Oxford – ‘public school boys [sitting] / in parliamentary green chairs / in the MCR’ (‘Self-Portrait as Othello IV’) – and Desdemona with a girl whose family thinks ‘it’s going to pass this fascination with the dark-skinned boy’ (‘Self-Portrait as Othello II’). The portrait becomes bidirectional: Othello’s story is shaped by the contemporary as much as the contemporary is shaped by Othello’s.

This mapping is made more complex by the power dynamic between the portraitist and the portrayed. In ‘The Picture and the Frame’, Allen-Paisant considers European portraiture and its selective conferral of importance: ‘The other African figures in the canvas occupy subservient roles, like pages, but they’re also comfortably there.’ Portraiture, like theatre, relies on bodily expression, and with that comes the interpretation or ‘making sense’ of the features and poses of characters. This is perhaps why Self- Portrait as Othello can read like a play, where speakers act and soliloquise while aware of the audience’s perception of their physicality and presence. Allen-Paisant has crafted a memorable collection with great emotional and intellectual span, while maintaining a linguistic playfulness that enriches its reading.

Similarly radical but vastly different in method is Nicole Sealey’s The Ferguson Report: An Erasure. Using the US Department of Justice’s investigation of the Ferguson Police Department’s racist policing as a source text, Sealey mines a sequence of eight compact poems from the report’s eighty-four pages. The report is not completely redacted but struck out and left in a barely legible light grey: what remains is a constellation of letters hovering in a sterile field of legalese. Words are chopped up, their forming obstructed by the report’s unstoppable procession, which both hastens and dampens the pace at which the text is read. Hastens, because the number of words on each page is sparse. Dampens, because each word is spelled out in slow motion. Indeed, Sealey returns repeatedly to suspended moments where violence threatens to manifest:

In the buses, next to the lot

across the street: a rustling

like backtalk: a deer. The animal,

out of nowhere, flees

seconds too late—a design

oversight assigned

to that particular beast.

(‘pages twenty-two to thirty-four’)

Sealey’s syntactic turns as well as her use of neighbouring repetitions of sounds (‘lot’, ‘across’, and ‘backtalk’; ‘design’, ‘oversight’, and ‘assigned’) wraps the text in a constrictive mesh. Fear is the dominant emotion. The sequence is populated with animals in panicked or agitated states: ‘Horses, hundreds, neighing—’, birds flying ‘low and patternless’, a dog choking on a leash, a fleeing deer. As the sequence progresses, the police appear as an ominous, agglomerated ‘they’:

Our heads twitch,

birds watching for what might

be stalking. Right before

they deploy canines to bite,

there’s a pause between wails

in which you hear your shut

eyes dilate. Listen.

(‘pages sixty-five to seventy-seven’)

Physical actions are amplified in the world of these poems, and as a result their misuse by authority becomes achingly clear. In ‘pages thirty-five to thirty-nine’, the ubiquity of police violence is hammered into focus as Sealey cycles through different uses of the word ‘force’: ‘use-of-force. Force / of habit. Of nature. Force / feed. Force down.’ The speaker, part of the ‘us’, is an incisive witness who is equally tethered to the living and the dead: ‘I’ve been trying to scrape / up what I remember:’ (‘pages forty to forty-nine’), and in the book’s concluding lines: ‘With an ear / to the glass, I remain silent. / Anything you say can and will be—’ (‘pages seventy-eight to eighty-four’). The poems are bolstered by a highly specific voice that is at once elegiac and potent. Just as Sealey’s erasure leaves the source text and its damning conclusions faintly visible, violence against Black people in the US remains a continual reality that cannot be erased from view. The excavating process of the book thus becomes a way of pinning down this ‘anonymous’, ‘temperamental’ history.

At the end of The Ferguson Report, Sealey offers what she terms ‘lifted poems’, an encore of the poems presented in ‘standard form’ with punctuation and line breaks (these are the versions quoted in this review). Freed from the gravity of the source text, these poems display in open air both Sealey’s astonishing commitment to exactness as well as how dramatically the erasure form reframes the work. Immersive is not an adjective typically used to describe books of poetry, but the collection’s visual power and lyrical rigour secures itself as a one-of-a-kind, declarative work.

Fred D’Aguiar’s For the Unnamed, whose full title is For the Unnamed Black Jockey Who Rode the Winning Steed in the Race Between Pico’s Saro and Sepulveda’s Black Swan in Los Angeles, in 1852, is about a more figurative kind of erasure. The historical omission of the Black jockey’s name in a well-known and otherwise well-recorded horse race becomes a platform of imagination for D’Aguiar. The collection is a play in verse: each poem’s title is named after one of the horses, jockeys, trainers, owners, etc. as indicated by a dramatis personae. The book’s epigraph quotes the preface of Alice Notley’s The Speak Angel Series: ‘There’s no nowhere for something to become nothing’, which in the original continues ‘I offer a future made of recombination like a collage, a pasting on of things by a massive regrouping of the dead and alive in order to begin again’. D’Aguiar too is regrouping, reconstituting the half-lost story of Black Jockey while prodding at parallels that are at once uncanny and revelatory to a modern reader.

At centre stage of the collection’s narrative is the relationship between Black Jockey (shortened to B. J.) and Black Swan, the black horse B. J. rode to victory against Sarco. Given that the race happens pre-Civil War, there is an uneasy parallel between the racehorse’s designation as property (owned by Sepulveda, an aristocrat) and slavery’s dehumanisation of Black people, which has rippling implications even for the freed man. ‘I become you and you become me,’ Black Swan says to B. J. when they first meet, offering a pact. As their bond strengthens, the line between horse and human blurs: ‘we must become each other / run from how others see us / if we’re to be true to ourselves’ (‘B. J.’), and later, ‘We’re conjoined and as scrambled as two creatures can be’ (‘Black Jockey and Black Swan’). The anthropomorphisation of the horse can be read not purely as a theatrical device, but also as a way to question definitions of personhood that, as history demonstrates, are more mutable and morally susceptible than one would like to believe.

The dual meaning of race is a linguistic coincidence. Race in the competitive sense comes from Old Norse rās, while race in the ancestral sense comes from Italian razza. Other than this semantic connection, D’Aguiar offers others that are more subtle. The racetrack and the spectacle of racing have an undertone of panic and conjure images of escape.

Indeed, for Black Jockey, racing is a way to ‘run from my hunters, from those who see me / as obedient, pure labour for free’ and to ‘escape what they do to black / people in this land’. The symbiotic relationship between rider and horse is not a frictionless one. There is also dramatic irony: ‘If that’s all you can do with me is say how much / I’m like you for being stock and enslaved, then, yes, / Damn right it’s a fight!’ (‘B. J. & Black Swan’) This meta-commentary is not simply humour but also a function of the book’s earnestness and clarity in what it hopes to achieve. Near the book’s end, three omniscient narrators (‘Call, Calling, Called’) converse quite transparently about the book’s conceit:

Called

What are we good for?

Call

Naming the dead.

Calling

They don’t care.

Called

What’s the point?

Call

For the living; for us; anyone who cares.

Called

It's a thankless task.

('B.J. & Ethel')

Throughout the collection, D’Aguiar crafts brilliant, exhilarating moments with thoughtful uses of the line. One of many examples include, ‘it may be the scissors of History bent / On cutting Black people out of its annals’ (‘Ethel’). Black Swan’s monologue that begins with ‘I run from history, more, tiptoe’ (‘Black Swan’) is particularly stellar with its rigorous yet propulsive structure and lines that lengthen and complicate as the monologue gallops forward. There are a few sections that feel a bit loose and held back by expository detail, which seems inevitable for a poetry book of 118 pages.

This may not be an entirely fair criticism however, given that the book is one that works through accrual and narrative mirroring, to the extent that it is difficult to isolate independent lines and take them at face value. However, D’Aguiar’s skill at generating narrative and lyrical momentum persists throughout, and together with a pithy sensibility for unuttered stories both large and small, For the Unnamed is an accomplishment that deserves repeated readings.

Eric Yip’s poems have been published in The Poetry Review and Best New Poets. He won the 2021 National Poetry Competition and was shortlisted for the 2023 Forward Prize for Best Single Poem – Written. He was a Poetry Society Young Critic in 2022.