Material Lacquer: Chelsey Minnis talks to Amy Key

I was in the Swiss mountain village of Grindelwald in August of 2018 when I opened my Twitter app and saw that the US poet Chelsey Minnis would be giving a reading in London, at the invitation of the Poetry Society. I screamed and my mum said, ‘Whatever’s happened?!’ and I said, ‘Chelsey Minnis is coming to England!!!!’ I didn’t have to explain who Chelsey was; she knew it was a huge deal for me.

Minnis grew up in Denver, received a BA in English from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and then studied creative writing at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop alongside the poets D A Powell and Jane Yeh. She has published four books of poetry, Zirconia and Bad Bad with Fence, andPoemland and Baby, I Don’t Care with Wave.

Minnis is perhaps the most emblematic writer of the ‘Gurlesque’ poetry movement, which included Ariana Reines, Matthea Harvey and Cathy Park Hong. Lara Glenum describes it in terms of ‘burlesque, [where women poets] perform their femininity in a campy or overtly mocking way’. Sam Riviere wrote that Minnis is a ‘purveyor of an enhanced, mordant femininity, recording the simultaneous disintegration and amplification of glamour as it enters a disaster zone, “a shimmer like sequins flushing down the toilet”, through an unequalled abundance of decadent, obscene, renunciatory images’. Her poems can be read as audacious and defiant, but behind the bold façade a vulnerability is contained and nurtured.

AK: I first encountered you by reading ‘Cherry’, a poem which seems to eroticise a wooden floor. Its imperfections are valorised but they unsettle too. That poem changed my life. It was the first poem I experienced in a physical way. It was almost like how there was a time I thought I’d lost my virginity, and then it turns out I’d not – I only discovered when the real thing happened. I was vibrating with the sense that this poem was the real deal. I was on my knees, then lying on the floor of this poem, trying to get as close to it as possible. Have you ever had a similar experience – in your own writing, or in your reading?

CM: This is a very nice compliment/question! Sometimes I want to jump up and move around right after I write a line I like, so I guess I sometimes experience the writing as physical? I don’t know if this is relevant but I’ve been learning a little bit about ASMR. Do you know about it? I guess one theory is that it’s a type of auditory synaesthesia. Anyway, I do have it and I’ve been wondering how much of my poetry might have been inspired by trying to create a similar type of experience. I definitely never deliberately wrote about my ASMR, but when you have it, you do this thing in your head to artificially prolong the feeling of it, and some of my poems feel like they have that same almost masturbatory quality. It’s like trying to keep bouncing a balloon in the air so that it doesn’t hit the floor.

AK: I am now deep into ASMR’s Wikipedia page, where it says ‘ASMR is described by some of those susceptible to it as “akin to a mild electrical current… or the carbonated bubbles in a glass of champagne”… it makes me consider the ‘rumble in your champagne’ imagery of your poems somewhat differently. Reading Zirconia and Bad Bad in quick succession was the most exciting poetry reading I’ve done in my life. I loved the directness of your writing, what I experienced as a kind of linguistic tantrum, the fetish for simile and appalling glamour. I loved how excessive is was – the layering on of images a kind of gluttony. I loved those things so much I couldn’t quite see beyond them. In recent years I’ve read and re-read your work and, when I think of a poem like ‘Primrose’, I’m struck by how in using the decadent images – the ‘corsages of gunshots’, the placing of a ‘flower behind my ear / as I beat gentleman rapists’ – you evoke a kind of pancake makeup on a movie star’s true face. I read ‘Primrose’ and I am winded by it. The vulnerability in your writing is well concealed by the excess, but for me, there lies its power. Could you talk about whether that’s an intent?

CM: Well, I’m not sure, but I can say that you seem to be talking about the poem as a kind of performance and that seems right to me. I also like when you say ‘I loved those things so much I couldn’t quite see beyond them’ because I have that experience a lot – where I’m not as interested in what a work of art is trying to do or say but am obsessed with some detail. For example, I might watch a scene in a movie and not be able to appreciate anything except the feathers on a hat. I’m thinking of Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich. She wears a lot of things in that movie that are totally paralysing to my critical sense. So, yeah, if I could write a poem that contained a really good feathered hat, then I’m probably happy with that. I wouldn’t ever say that I’ve written a poem as good as Shanghai Express is as a movie, but I think I’ve tried to write poems that had some nice details in them that might be enough to blind you to the poem’s overall failure.

AK: I strongly relate to the tendency to be distracted and enamoured by a detail so much that I don’t pay attention to the bigger message of a work, but it will be that detail that makes me return to it – meaning accrues. That I can go back to, say, Bad Bad and re-read a poem like ‘Foxina’ and become newly obsessed and add it to my mental inventory of The Best List Poems. It’s not failure, it’s like a brilliant switcheroo to be lured in by the lacquer of a poem and slowly come to terms with the underlying material of it.

CM: I like what you’re saying.

AK: When I first came to your work, you were introduced as a poet of the ‘Gurlesque’. To what extent were you aware of this movement in poetry? Did you identify with it?

CM: I really saw the Gurlesque as this nice thing wherein some women were being introduced and grouped and explained. That seemed like a nice recognition. But I really didn’t pay too much attention to it because I felt like I should just write the poems and let other people figure that stuff out.

AK: Did you feel that recognition helped redress a gender imbalance in US poetry? White men have been very dominant in British and Irish poetry since the dawn of time.

CM: I haven’t followed it enough to know if it made a difference but I hope so? That’s a really important thing that needs to happen.

AK: I made the mistake of reading your poems as ‘anti- poetry’. When we met in London I realised I’d mistaken the speaker for the poet. You said then that writing poems is your greatest decadence. Is part of that decadence the sense that poetry isn’t always available to you? There is luxury in having the urge, conditions and confidence to write?

CM: I hope I didn’t make you feel like you made any mistakes in the way you read poetry though! I’m just not very good at facing up to what I write. I do it as a sort of tantrum. I put out all these rages and then am like, ‘Oh, I didn’t really mean that!’ It’s terrible, I guess.

AK: I wonder if you could say a bit more about the connection between writing poetry and shame? Even as a 40-year-old I’m still embarrassed about masturbation, and that is entirely shame-driven. When writing a poem, I’m often ranging about for ‘that feeling’ which isn’t a masturbatory pleasure but it’s a very specific pleasure that no other activities replicate. Sometimes I can get into that zone, others I’m just not feeling it.

CM: I’ve been thinking about shame quite a bit lately and wondering about something that happened to me in seventh grade. I went to a Catholic school called Most Precious Blood and that doesn’t seem reasonable to me, but anyway, I wore something to class that wasn’t in the uniform code – a beret. My teacher, Sister Barbara, must have alerted the principal because she (Sister Mary) came charging into the room and tore the beret off my head while yelling at me. Anyway, I’ve been sort of wondering lately if that wasn’t sort of an original lesson in the shame of self-expression?

Rather than sex, or anything erotic, I mainly get the ASMR from really banal social interactions, although there’s this amazing video online of Elizabeth Taylor doing her makeup, and I get it from that. But that’s Elizabeth Taylor and she’s amazing.

AK: I love Elizabeth Taylor! She actually brings me to my next question. Your latest book Baby, I Don’t Care takes inspiration from classic films. I’d really love to know more about how you turned films into poetry. I also know you are working toward becoming a filmmaker, and you write screenplays. Could you talk a bit about that, and reflect on how and whether your poetic practice might find its way into your filmmaking? I’d also love to hear more about your screenplays – I seem to remember there is one about a haunted sea world?!

CM: I’ve often written while I watch movies. I used to bring a pen and notebook to the movie theatre with me and would scribble things down in the dark. In Baby, I Don’t Care, I copied down lines of dialogue while watching TV and later I scrambled them up and then tried to put them together in a new way. I tried to choose lines that weren’t immediately recognisable. I also wrote some lines myself, which makes it even more confusing.

I’m still learning how to write the screenplays. I’m sort of in a middle stage. The first stage was when I didn’t know what I was doing and as a result I wrote some good things. Then I started to figure out what I was doing and the work immediately got much worse. Now I’m hoping that I’m maybe able to deliberately do some good things and hopefully also accidentally do some good things. I don’t think my poetic practice has come into it too much because I tend to be very concerned with structure and format in the screenplays whereas I’m sort of sloppy and blind with poetry.

I would love to produce and direct my own microbudget movie, but I still have a lot to learn and then I also need to get up the courage because it’s quite terrifying. The second screenplay I ever wrote was a horror movie called The Tank.

The Tank: A gold-digging cocktail waitress and her deaf son inherit a haunted mansion built on the site of an aquatic theme park, but before they can start a new life, they must reckon with the ghost of a deadly killer whale.

It also contains a restless swimming pool, a possessed waterbed and a vengeful mermaid. The third movie I wrote was a romantic comedy (screwball) called Railroad Ties.

Railroad Ties: A suicidal writer hopes to salvage his life by writing a blockbuster action screenplay with a naive ex-dominatrix before their cross-country train reaches LA.

In that one there are also some aquatic dancing sequences, a supper club and a striptease involving a bear suit. I do want to say that I wrote these before the election (same asBaby, I Don’t Care) and so the things I’m writing now are a bit different!

AK: I would camp out on the pavement outside a cinema to be first in line to see these films! (I am really obsessed with sea life, particularly giant manta rays; please cast a manta ray in The Tank.)

CM: Well, I think a manta ray could have its own movie? Maybe I’ll work on that. I would give you a free ticket to the premiere so you didn’t have to camp out on cold pavement!

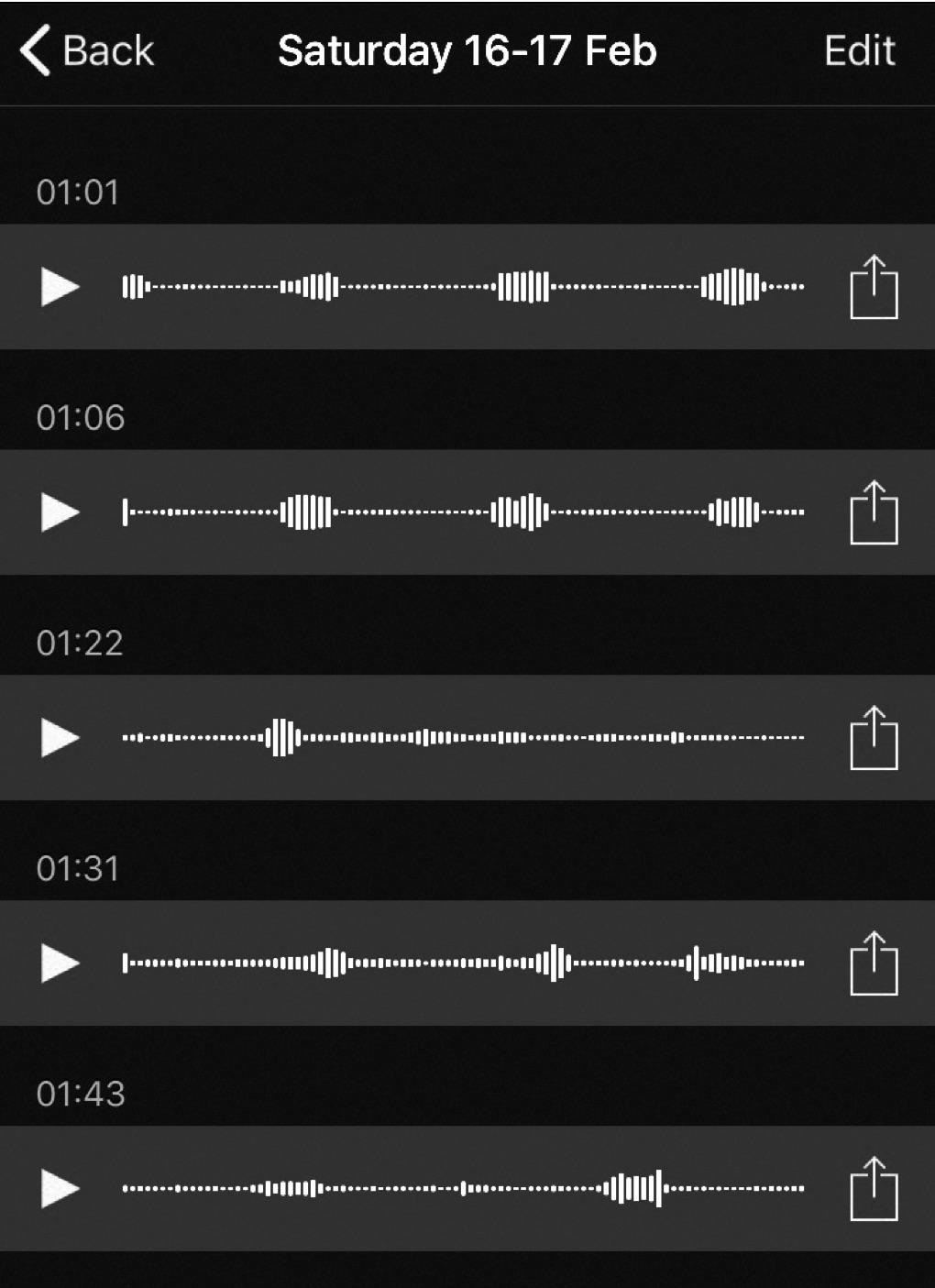

AK: I don’t think I can avoid asking you about one of the most striking hallmarks of your earlier work – the extended ellipses. They’ve been described as bullet holes in the work, or strings of diamonds… Could you talk a bit about how you used ellipses to bring a form to your poem and why they are no longer present in your work? (Full disclosure: I’ve been using an app called Sleep Cycle. It monitors your sleep and records any snoring. I sleep alone, so it’s encouraged an acceptance of how much I snore and how strange it is to eavesdrop on your own sleep. I feel very tender towards my sleeping self, making these alarming noises. When I first looked at the recordings I thought, ‘It’s a Chelsey Minnis poem’, so my position is now that the ellipses are translations of my non-snore sleep!)

CM: It’s hard to explain the ellipses but I can tell you that maybe they were a crutch and so the reason they’ve dwindled is that I decided I didn’t need them so much? Also, I think I’ve gotten lazy about them? Also, they seem to draw attention to themselves and I don’t always know what to say about them? Also, I’m just fickle? At the very least, I’m inconsistent. Now this snoring chart is what I’m talking about! Let’s have this whole interview just be X-rays and printouts! I like how you feel you have to accept how much you snore. I agree, though, that you should be tender to your sleeping self and also to your waking self! I don’t know much about it but it seems like you have good variety in your snoring. Also, maybe they’re sort of small? They don’t seem like they could be very loud.

AK: I’ve just watched the Elizabeth Taylor video and there’s a moment where she lowers her eyelids a tiny smidge and she gives herself a look like how a cat can sometimes look at you. It’s like she’s saying to herself ‘Not Too Bad!’ It’s so satisfying! Is it wrong to say I find Catholic school names very compelling? Most Precious Blood sounds really goth! But I understand only too well how being shamed and feeling shame can have this strange effect that makes the urge to self-express more potent.

CM: I totally understand why she looked at herself like that, though, because she was a bit gorgeous. If I looked like that, I would be giving myself the eye all the time! But yeah, there’s something sort of unselfconscious about it which is what makes it so luscious. Also, did you know that Elizabeth Taylor supposedly had a genetic mutation that gave her a double row of eyelashes?

I don’t think it’s wrong to say that Catholic school names are compelling! Catholic imagery definitely contributed to the whole gothic thing we were talking about in ‘Primrose’. I do want to say that I realise that what happened to me (Sister Mary tearing off my beret) was actually pretty funny, even though it was sad. When I think about all the abuses of the Catholic church that are being exposed now, I realise I got off pretty easy with just a minor case of humiliation. And clearly I was out of line. I was a subversive force that needed to be stopped!

This also brings me to want to say that almost any trauma I mention or anything I talk about is unimportant compared to what’s happening in America these days. We have to elect a Democratic president in 2020, and in Colorado specifically we need to unseat the horrible Republican Cory Gardner. So anyway, back to your question about shame making the urge to express one’s self more potent – it sort of raises the stakes and makes the whole enterprise more tempting. Maybe I enjoyed provoking Sister Mary into a rage just by wearing a beret? But also, I’m thinking lately that repressed self-expression might feel worse than shameful self-expression. A friend and I were talking about how repressed artists can sometimes turn out to be the biggest fascists and so I’ve been thinking about that. Maybe I need to be more supportive of even small acts of creativity when I see them.

AK: I hope that means more supportive of yourself, too?

CM: OK! Let’s try it.