‘Telling You The Truth, As Best As I Can’. Selima Hill and Julia Copus in correspondence

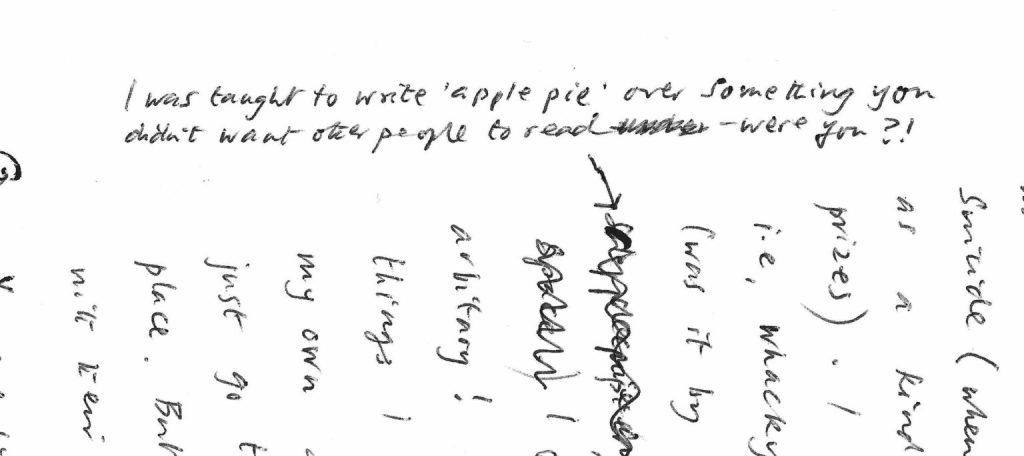

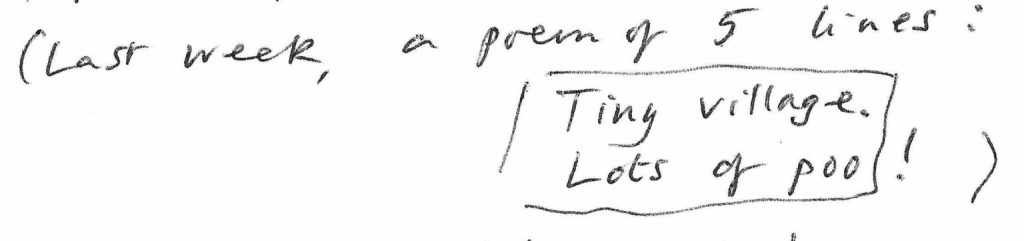

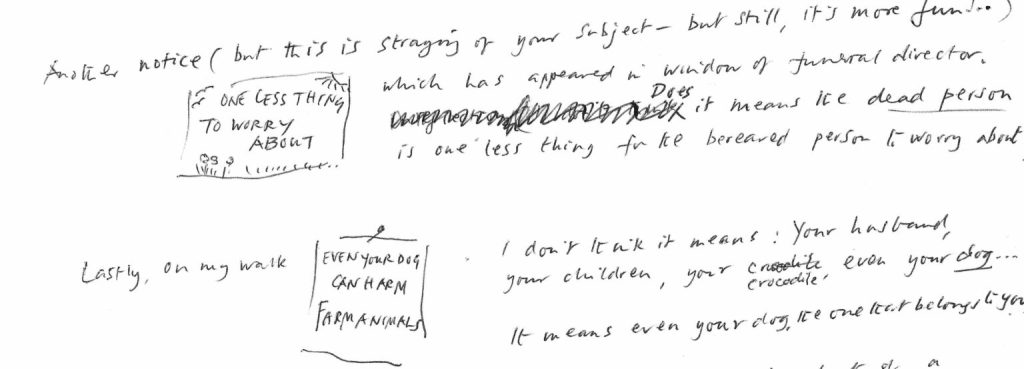

Selima and Julia first met in the Ladies toilets on the top floor of City Hall, London. They were there for the National Poetry Competition presentations in 2002, when Selima was part of the judging panel and Julia had been awarded first prize. On that occasion they had a brief conversation about hiding in toilets but didn’t meet again until three years later when Julia succeeded Selima as Royal Literary Fund Fellow at the University of Exeter. They have corresponded on and off ever since. This interview took place by post between their homes in Dorset and Somerset in the spring of 2021, with Selima’s handwritten responses arriving on unlined A4 paper, with many marginal notes, addendums and arrows, and the occasional sketch to illustrate a point.

Julia Copus: You opened one of your most recent pamphlets with a little gem of a poem by Hilaire Belloc called ‘W for Water Beetle’, in which he describes the beetle astounding everyone by walking on water with ease, before concluding ‘But if he ever stopped to think / Of how he did it, he would sink.’ That makes me hesitate to ask you to think about how you do it, but perhaps you could give us a few clues. You’ve published over twenty poetry collections to date since your first came out with Chatto in 1984. That rate of production suggests that the poems come to you very fast. Do they?

Selima Hill: Let me tell you about a recurring nightmare I have: I am at a reading or a party and open my mouth to speak. Something like a soft pink worm wiggles up my throat and across my tongue; before I can close my mouth it unspools itself out into the room, streaked with blood. It’s like spaghetti, it keeps slithering out and I realize with horror it is going to carry on until all my entrails are uncoiled and I’m turned inside out and I die!

JC: It sounds terrifying! I’ve also heard you talk before about how you write very quickly and then ‘cut, cut, cut’. It seems to me that the sense of expansiveness and spontaneity you create in your poems is hard to achieve: many, if not all, writers have an internal censor watching over what they do. What is the process of writing like for you?

SH: You mention ‘cut, cut, cut’. Maybe my word, but I don’t like it. Too negative. I would say first ‘loosen, loosen, loosen’ and then (after the poem has sat on its own in a drawer quietly for a few weeks, or months) ‘tighten, tighten, tighten’. So it’s nice and clean. Maybe one tenth of the original length remains. At the risk of sounding pompous and nonsensical, I suppose I could say I aspire to silence. Silence not as nothing but as everything. Not a retreat but on the contrary, a touch, or a touching. First listening, then touching.

Thinking of silence in the context of autism, it is maybe not irrelevant that I was mute when I was in my twenties, although I didn’t feel it, and continued to write – and to play chess! I suffered what was dramatically called then (the Sixties) ‘catatonia’: i.e. stupor, mutism and posturing. (‘Posturing’ means not moving, and sometimes getting ‘stuck’ in odd positions…)

JC: And can you say something about how a poem might first arrive for you – out of the silence you’re reaching for, as it were? Do you start with a phrase? An image?

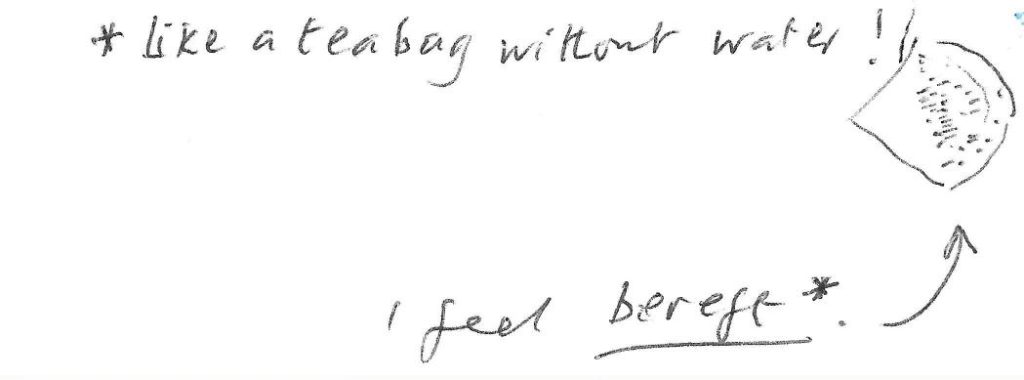

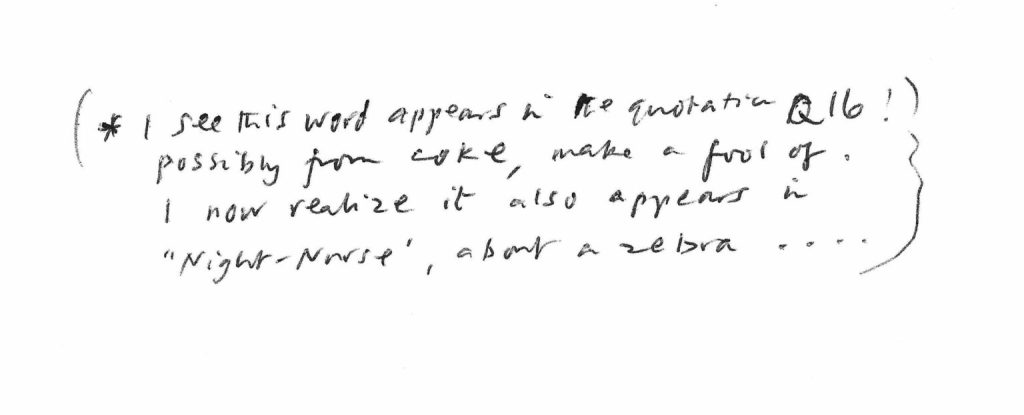

SH: I write more or less non-stop so I don’t ‘start’ exactly. If I am not writing something I feel bereft, like a teabag without water! Let’s look at my last sequence [‘The Night Nurse’]. My sons were on my mind, more than ever. Then a young man passed my gate (my cabin is on a coastal path) so I used that moment as a sort of magnet to stick all my thoughts about sons onto. The tone of voice is the guiding thing, I think; then the rest follows. Like unreeling a fishing-line. Who was it (Margaret Atwood?) who said ‘autobiography is not true enough’? Anyhow, I invent more about the young man in order to say things safely, in fiction, that I am inhibited from saying out loud, or even thinking. Or maybe I do start with an image. I don’t know. It is all happening at once.

JC: When I was little, my stepfather told us this riddle, whose answer we kept forgetting and had to keep working out: ‘Brothers and sisters have I none, but this man’s father is my father’s son.’ Your poems often complicate the genealogical connections between people in a similar way. For instance, the two sections in Violet are titled ‘My sister’s sister’ and ‘My husband’s wife’. I’m wondering if this is a way of distancing your current self from other, former selves or versions of those selves. In ‘The Woman in the Salmon-Pink Underwear’, for instance, from your 2019 collection My Mother with a Beetle in her Hair, the speaker ends up sitting beside another woman, sharing chocolate kittens. I took this other woman to be a younger self – though it’s more than possible, of course, that I’ve misread it!

SH: You didn’t misread it, exactly, Julia – you are the world’s most ideal reader – but it was grounded not in a distrust (of other selves) but of warmth and a sense of amused fellowship with the selves of others. Another way of looking at it could be to say that we are all both ourselves and each other, with our shapeless breasts and loving husbands and plastic sandals – all in it together.

JC: I like that idea of a fellowship of selves. And you write a lot too about actual family relations. The ‘I’ in your poems describes relationships with her mother, father, sister, aunts and so on. She also talks about herself as a child, and as a baby, but never alludes to her own children (if she has any). Are there certain subjects that are off- limits?

SH: Off-limits – yes. My children; anyone who is still alive who would be identifiable; where I live. Partly to protect them, because it isn’t fair. They may feel hurt or misunderstood: I feel very strongly that ‘art’ is not an excuse to hurt people. I can change people’s genders, leave people out. It gives me freedom to make the reality more so. To make it cleaner, simpler. As Bohumil Hrabal says, the book is a book written by a stranger about ‘that great fantasy that is called reality’.

On the subject of ‘I’, let me refer to Iris Murdoch, the philosopher: ‘Love is the difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.’ (She doesn’t even say ‘someone other than oneself’…). Paul Celan wrote that he was ‘an I clarifying itself in the process of writing’. However, rather like Denise Riley, I think, he sees the poem as existential rather than epistemological. It (the poem) takes the poet ‘into its understanding’ then ‘releases him’ (the poet).I don’t approve of too much autobiography. And how far can we admire the writing but not the writer? Larkin, Lowell, Hughes, for example. But my only subject really is me. What other experiences do I have than my own? That is part of the sorrow of the human condition, that we can never really know each other. (See your own poem ‘Soft Parts’!)

JC: Another poem of yours, ‘Different Kinds of Honey’, ends with the line ‘I’m like a sort of spy, I suppose.’ You also say in that poem – and it’s a sentiment expressed in several of your poems – ‘but actually I like to be ignored’. It seems to me that many writers battle with wanting and not wanting to be seen – maybe poets especially. Can you say something about this question of visibility?

SH: I loathe being visible because I think I look wrong but I don’t know how. So visibility (exposure) is vulnerability, and vulnerability means vigilance.

If we look at visibility in the literal sense, I could add that I like light, as much as possible, but I do not like being something seen, so my cabin is full of mirrors, but all above eye-level so I can’t see myself!

JC: You may not like being seen but the world of your poems shimmers with visual detail. You were born into a family of painters. How much do you think that background accounts for your painterly attention to the visual?

SH: I prefer ‘sensory’ to visual. In fact things like weight, temperature, viscosity, smell, I would say, are also my subjects. I like facts. They are safe and stable.My parents and grandmother were painters (and I married one). How much of [being an artist] is cultural and how much is genetic, who knows? I do know that writing always felt more secret. My notebooks were more private than their sketchbooks. I also often wrote in code. (It makes me chuckle to think of some of my coded notebooks in my archive at Newcastle!)

JC: What you say about your fondness for ‘facts’ is interesting. I don’t think many critics have picked up on that. On the other hand, several have commented on your use of surrealist techniques. I wonder what you make of such descriptions.

SH: Don’t get me started on surrealism! I hate the thought of being ‘surreal’ – i.e. whacky, arbitrary, showy-off. I feel like I am the opposite of surreal. However, I can understand how, to other people, things I say might not make sense. Why should they? It’s my own sort of private synaesthesia. Poodles and bluebells, say, just go together, for me, like two notes in music; they fall into place. But why should that mean anything to someone else, with their own personal experiences of poodles and bluebells?

JC: It will mean something different to them, for sure. I’m wondering if the originality of your images – that freshness of perception – is linked in any way with your experience of Asperger’s syndrome.

SH: I might refer here to my earlier mention of synaesthesia and sensory processing – and I’d add to that my differences, if not difficulties, re proprioceptivity. I should say that I would rather be a sculptor than a poet. More physical, less pedantic, conceptual, neurotic and exposing.

JC: That makes sense. Lots of the scenes you create do have the feel of – if not sculptures then installations. There is a specifically dreamlike quality to many of them – a suitcase spilling its contents across the sky; a flock of knitted sheep standing guard outside a bedroom; a frustrated lover’s scream that ‘screams between us like a frozen street / with stiff exhausted birds embedded in it.’ This last one reminds me a bit of a De Chirico painting – the landscapes he painted, with tiny figures against a portentous backdrop that seems charged with energy and meaning. Do you feel you’re bending reality into a different shape when you write; of making it super-real?

SH: I agree that the relationship between dream, reality and text is a fascinating one, but I do not feel any kinship with, for example, Homer, Virgil, Dante, Bosch, Swedenborg, Blake, Novalis, E T A Hoffmann, de Chirico and so on in that way. I’m more of a Kafka fan. Or Katherine Mansfield, Sebald, Flannery O’Connor, Calvino, Statovci, Simic, Anna Swir, Ana Blandiana, Michael Longley, Elfriede Jelinek. Elizabeth Bishop even. I object to the idea of ‘bending reality into a different shape’. Different from what? I feel I am not bending but straightening or unfolding.

JC: Unfolding, yes, it does feel like that: as the poems unfold, hidden surfaces become unhidden; brought to the light. And in your sequences – many of which are book-length – often an idea or phrase or image is introduced in one poem and then picked up in the next, but approached from a different angle. The poems become like different facets of the same gem, turned this way and that to see how the light catches, so that the subject becomes fresh again to us, becomes defamiliarised. But there is usually also a narrative line (however fragmented) running through each sequence. Do you plot a sequence’s direction before you start writing it, or is it more a matter of being led by the images – of just getting on the train and seeing where it takes you?

SH: Don’t ever go to a film with me: I can’t follow plots! Partly (more pathologising) because I can’t recognise faces. Prosopagnosia. This does not apply, obviously, to the written word. But I can’t follow plots in novels either. Also, I don’t like flickering screens and poetry is shorter and more portable! So, in a word, no, I don’t ‘plot’ sequences. Again to pathologise, I am ‘perseverative’: I just go on and on. Plot, no; patterns, yes. I love crosswords, for example, and codewords, wordsearches, quizzes, Dumb Crambo, Categories, jigsaws, mancala, solitaire, Qwirkle – anything that requires concentration and focus and a kind of purity and pedantry.

Your train image is a good one. It is hard to change tracks. My work is about surprise, exaltation, perplexity, disillusion, disintegration, broken promises. Always the same. Like Bela Tarr says it is ‘always the same film’ that he makes, whether it’s Sátántangó, The Turin Horse, Weikmeister Harmonies. Unlike a film director, however, there is no-one I have to cooperate with. Like a singles tennis player, the writer is on their own. On their own with a ball. They just have to keep it in the air.

JC: Perhaps related to this, the syntax of your poems is deftly sustained; in the longer poems it’s organised over many lines or stanzas, taking a number of twists and turns along the way, often in a single sentence. The effect is one of suspension – of something being held afloat in the air, or of a breath being exhaled with such poise and evenness that it carries us right to the final line. There’s great skill involved in managing the pacing of such a sentence and its thoughts, and in coordinating subject, tense, case, number and so on. Your rhythmic control is also striking, yet it’s completely unobtrusive: most of your work sings with a gentle iambic pentameter pulse – often divided across lines so that it never sounds monotonous. Does the patterning of language hold a particular interest for you? I’m wondering, for instance, if you studied Latin.

SH: That is uncanny. Yes, I read Classics, got fed up with all the men and the wars, and changed to moral sciences, where even more of the tutors and the writers were male, needless to say. (I can still hear myself declaiming, at the Latin Orations my creepy Classics master drove me to Southampton to compete in, ‘Quadrupedante putrem sonuit quatit ungula campum.’1… and, at another event ‘ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ’2…) I have also learnt, or tried to learn, without much success, Ancient Egyptian, Finnish (Tove Jansson – have you read ‘The Listener’?), Mongolian (both the old script and the new 1941 alphabet with Cyrillic characters), Romanian, British Sign Language, Icelandic… I lived in Iceland for a bit, where they still – being an island, I suppose – talk like the sagas! It’s easy to understand. Also pig Latin, which I enjoy speaking very fast, in order to follow and keep control of both the rhythm and the structure you refer to here. It’s the juggling, isn’t it? Keeping all the balls going without dropping them. Forming a pattern in the air without touching the ground.

JC: You’ve talked elsewhere about your love of Romania, and I can see points of contact between your work and that of poets like Marin Sorescu and Mircea Dinescu. Do you feel a connection?

SH: Writers writing under totalitarian regimes (Romanians under Ceaucescu, for example) learn to encode their work, as, I suppose, I have done. I don’t follow Auden when he says art is ‘born of humiliation’, or Mark Twain – ‘The purpose of art is to alleviate shame’ – but I would argue it gives us a space to say what we want to say. And, as Genet says about Giacometti (why do I keep quoting male writers?), ‘Each man guards in himself his own particular wound, different in everyone.’ For me, ‘art’ doesn’t exactly ‘alleviate’ anything: it makes it closer.

JC: You’ve said in the past that you have difficulty forming relationships. Publishing is all about communication; about connecting with your readers. Is there a sense in which communication is easier – more straightforward – for you through writing than it is in real life?

SH: Writing is real life – even if only a part of it. Writing is real, concepts are real, words are real, readers are real. I like what Jenny Odell says somewhere (or was it Cage?): it’s about looking at reality rather than through it. Or, as I think I said before, writing feels like touching. (I say that as someone who is hyperlexic – I could read fluently when I was three, apparently – but hates being touched, particularly brushed against.) In some ways, writing is more challenging – and that is precisely why I like it. To have the comfort, silence, space to be as accurate as possible. But even words, being conceptual, are a kind of violence (a violence towards silence).

Of course publication is a different thing altogether. Why oh why do I publish? It is true I value the fellowship of my readers – but only if they stay away and remain strange and imaginary. (Except you, of course, Julia!) It’s a bit like someone coming barging into your bedroom, isn’t it? Neil (Astley), I should stress here, treats me with great tact and understanding. He knows just how to handle me. So I am very lucky.

Maybe I can mention here another aspect relating to this: poetry readings and the look of the poem on the page. The carefully balanced line-breaks, the patiently manoeuvred stanza-breaks, the exotic looking caps, the spellings, the precarious punctuation – all that disappears in a reading. The shapes on the page are, for me, no less important than the sounds in my head. (Yes, I know poetry was originally oral.) Furthermore, poetry readings suggest – how can they not? – that the reader we have before us is the first-person protagonist of the poem she is reading. Again, the elaborately crafted fiction is shattered. We are distracted and misled by the physical presence of the poet-reader.

JC: What you say here ties in, perhaps, with your earlier comments about your aversion to self-visibility. Even so, much of your work contains a sense of urgency – an earnest desire to communicate. Your poem ‘Much Against Everyone’s Advice’ begins, ‘Much against everyone’s advice, / I have decided I must not be put off any longer / from coming into the yard / and telling you the truth, as best I can.’ Is ‘the truth’ what you’d like to give your readers (if indeed you have a reader or readers in mind when you write)?

SH: It is my kind of truth, true for me, but why should it be anyone else’s? I am constantly being astonished by how a bucket, for example – my bucket – is understood by someone else and responded to by them as if it was their bucket. As if we understand each other somehow. Weird. My associations and elaborations are all individual, private, personal, intimate – secret, almost. We do not share them; or not all of them, certainly. So I’m always surprised by how readers nevertheless do respond to another person’s work. Maybe it is the passion powering the content that readers connect to, rather than the content itself. A mysterious reciprocity seems to arise.

The reality on the internet, by contrast, is other people’s reality; it’s reality for others, not for ourselves. Our attention is abused, exploited. We are left dissatisfied, dishonoured, anxious – and more, not less, alone.

JC: Well, however private those ‘associations and elaborations’ are, they nonetheless connect deeply with readers: your work bristles with similes and metaphors that feel charged with meaning (envy is like a swimming pool, with ‘its room-sized weight’, for example), yet I get a sense that they aren’t driven by a methodical search for alikeness (as in one thing equals something else because of some logical connection). Do they arrive instinctively or are they harder won?

SH: My images are as exact and as honed as it is possible for me to make them. It is like a note in music: either it is right or it is not. I can’t say why. And nor do I expect other people to understand either. It is just how it is, if I attend to it (whatever it is). If I give something my attention, then I see it is there, and enough, always – the texture, the smell, the endlessness of it.

And a final thing about metaphors: my father was said to have a ‘sweet tooth’. I thought this tooth was an actual sweet, a barley sugar, in fact, that was sharp like a translucent flint and very, very frightening.

Selima Hill is the author of twenty collections of poetry. Fairacre Press have just brought out Selima’s From Angel to Zebra, an alphabet book written for adults with illustrations by Tim Nicholson, and throughout 2022 will release a series of twelve monthly pamphlets, What to Wear in Bed, available by subscription.

Julia Copus has published four collections of poetry and been shortlisted for the T S Eliot and Costa Book awards. Other awards include First Prize in the National Poetry Competition and the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem. Her 2021 biography of Charlotte Mew, This Rare Spirit, was a Spectator Book of the Year.

-

Virgil, Aeneid, VIII, 596 – ‘And the horses; hooves shake the crumbling field as they run’ – ed.

-

Homer, Odyssey, I. 1 – ‘Sing in me, muse, and through me tell the story’ – ed.