Roadmaps to Possibility

Chrissy Williams on three books whose formal experimentations offer innovative frameworks for exploring identity and connection

Chrissy Williams

-

Constellations

Astra Papachristodoulou

Guillemot • £12 -

Tear and Share

Leia Butler

Broken Sleep • £6.50 -

The Book of Penteract

Anthony Etherin and Clara Daneri (editors)

Penteract • £32

The first poem in any collection is perhaps the most important. It establishes the relationship with the reader, choosing whether to hold their hand or push them out the window. I think that’s especially true when setting forth an unconventional project such as Astra Papachristodoulou’s Constellations, a sequence of 88 visual poems based on the 88 recognised constellations. This collection takes the reader nowhere near the window, except to look at the stars.

The relationship with the reader begins even before the first poem though, with a ‘Suggested Reading’ that informs us: ‘Stars within a constellation are usually lettered from Alpha (α) to Omega (ω).’ We are given a chart of the Greek alphabet and a brief invitation to read the poems’ lines in Greek letter order (each line, we’ll see, is usually short and laid out in all directions on the page, running along the spokes that link each constellation’s stars). Although this indicates the author’s preferred reading, the tone is gentle and includes an acknowledgment that ‘the lines are flexible and the reader is welcome to mix & match the lines as they please.’ The poet can choose to be a dictator or a baffler, and this introduction strikes me as an ideal balance between the two, lightly defining the material project without excessive instruction.

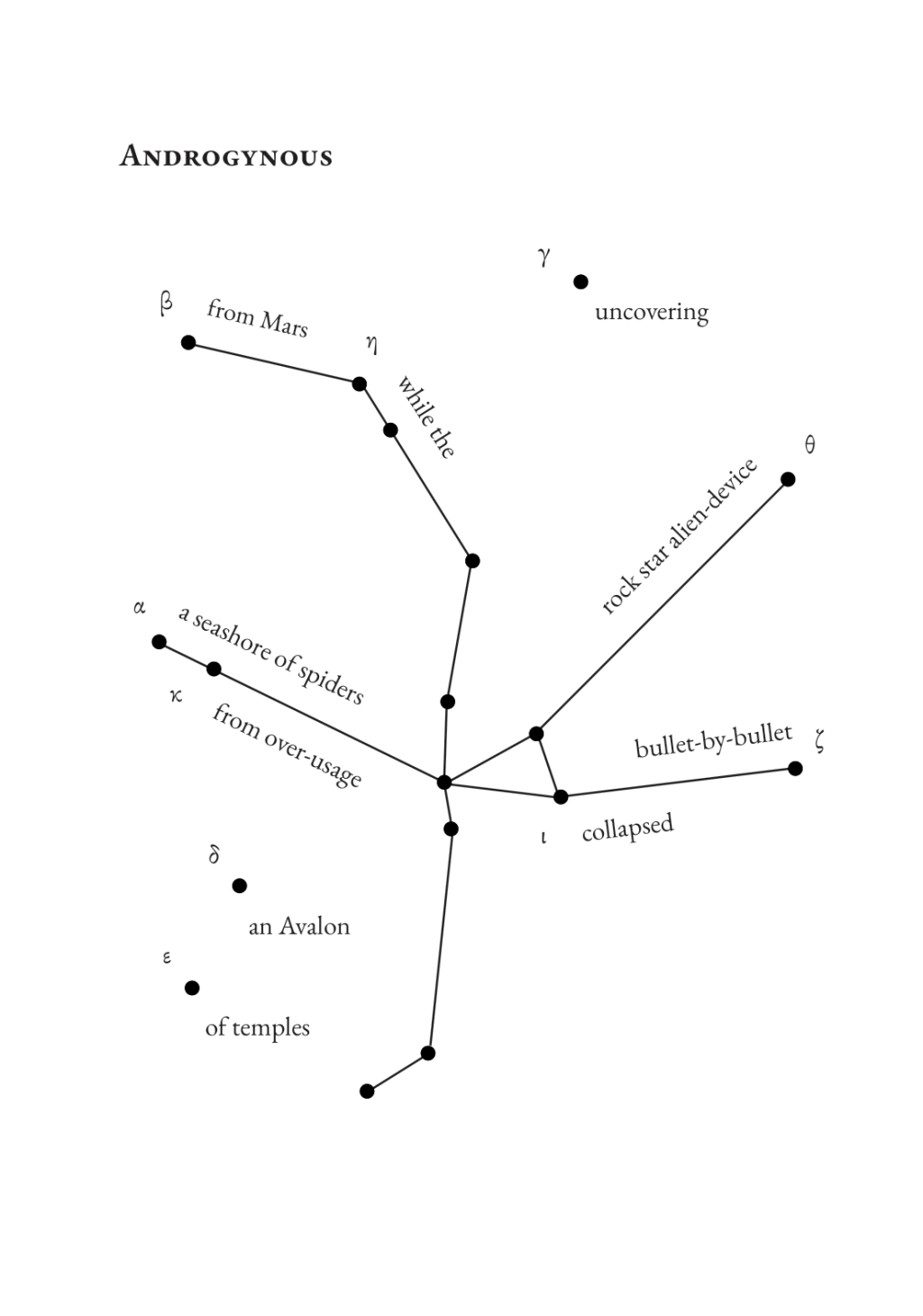

So, to the first poem. Laid out across the constellation of Andromeda, the ‘chained maiden’, we see snatches of text such as ‘a seashore of spiders’, ‘from Mars’ and ‘rock star alien-device’. Under the title ‘Androgynous’, it’s impossible not to go straight to David Bowie, but the references are subtle enough that they don’t steer the poem into a single track. We also have ‘temples’, ‘collapsed’ and ‘uncovering’ – there is something devotional here, and something ancient. ‘Androgynous’ lays out key themes and subjects for the book. Bowie is absolutely one, particularly with Ziggy Stardust in mind, but so is a sense both of celebrities as ‘stars’, and ‘stars’ as real people. There is a basal crudeness to the pun, but the poems aren’t played crassly – just the opposite. As their lines fan out across the sequence, immense perspective shifts freefall out from them, as we’re invited to conceive of any vast celestial body as an actual real person, and of any single human as a literal star, perhaps a dying star, hundreds of times larger than the sun, and thousands of times as bright.

When reading, I dutifully look at the Greek alphabet chart and read the lines of text in the suggested order, then I go back to see what happens to the poem if I ignore it. The suggested order for this first poem is the most satisfying in terms of making grammatical sense, but it is also possible to relax your eye across the whole image, taking in the words and phrases in a more kaleidoscopic way so they combine in the mind. The suggested order being so well established though, I find myself mostly sticking to it throughout.

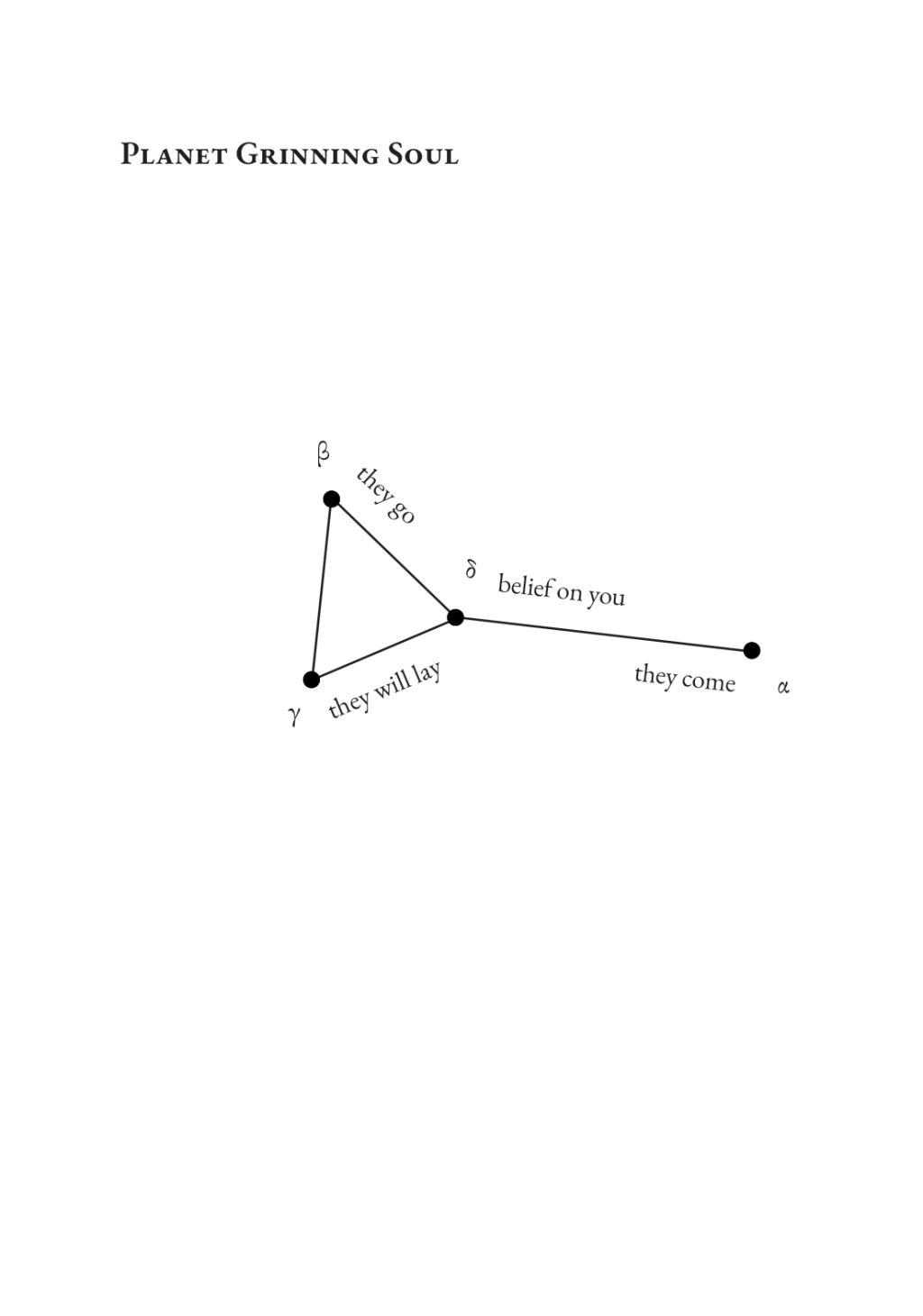

The second poem gives us a little Nadsat slang, bringing with it that sense of violence and subculture from A Clockwork Orange. It was obviously a huge influence on Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust period, but this feels more like an act of linguistic revelry than mere fan service. The third poem is a great example of how a more nuanced reading can occur if you read out of order. The poem’s four lines are ‘they go’, ‘they will lay’, ‘belief on you’ and ‘they come’. Remixing these lines in various ways does something quite interesting to the concept of belief, and cleanly enacts a poem’s ability to yield multiple readings whist remaining a single static object on the page. The opening lines of Bowie’s ‘Lady Grinning Soul’ are ‘She’ll come / She’ll go / She’ll lay belief on you’, and the subtle authorial tweak here, combined with the visual presentation, creates something able to stand alone regardless of the Bowie context, something I think the sequence does well overall.

Having established this form so well, it would be easy to stick to it for the whole sequence, but Papachristodoulou introduces other elements: silent lines and pauses, text-less poems, poems that invite the reader to label the constellation parts, join the dots, fill in the text themselves, and (as one title indicates), ‘Colour the Centaur poem using telepathy’ – all while mixing her own texts with snatches of heard and repurposed Bowie lyrics. This is a playful and moving sequence, and its imaginative scale is a delight, elevating it beyond its core concept.

We all know we’re not supposed to reproduce any pages from a book without the publisher’s permission – the rights notice on the imprint page tells us so. It’s curious in this case, however, as each poem in Leia Butler’s pamphlet Tear and Share is presented with a dashed line down the centrefold, and the reader is invited to literally ‘tear and share’ the poems. You may not be able to reproduce these poems without permission, but you can rip them out, rip them up, or tape them to lampposts with the publisher’s and poet’s express blessings. It’s an interesting idea, and the whole pamphlet is an explicit response to the COVID-induced loneliness we’ve all experienced at some point in recent years. There are QR codes at the top of every page which guide you to a Dropbox folder, where you can upload a photo showing where you’ve left each torn-out page. It’s not just about the act of sharing the work in real life then, but of feeding back to headquarters, and participating in something that feels more communal than the usual solitary act of reading.

The poems themselves live in a lonely space, considering distance and separation, with poem titles like ‘Distance Decay’, ‘Sanitize’ and ‘Nospaceforspace’. The style employed overall is quite fractured – a lot of irregular line lengths and indentations, enjambments flowing down the page. Some of the formal choices are literal reflections of the text. For example, the word spacing is increased in a line like: ‘and the gap gets wider’ in ‘Distance Decay’; or a full line space is added between the single-word lines ‘separating’ and ‘you’ in ‘Pick your path’. I know some readers will find the clarity of these formal choices pleasing, but the flip side is that it can make some of the lines feel predictable.

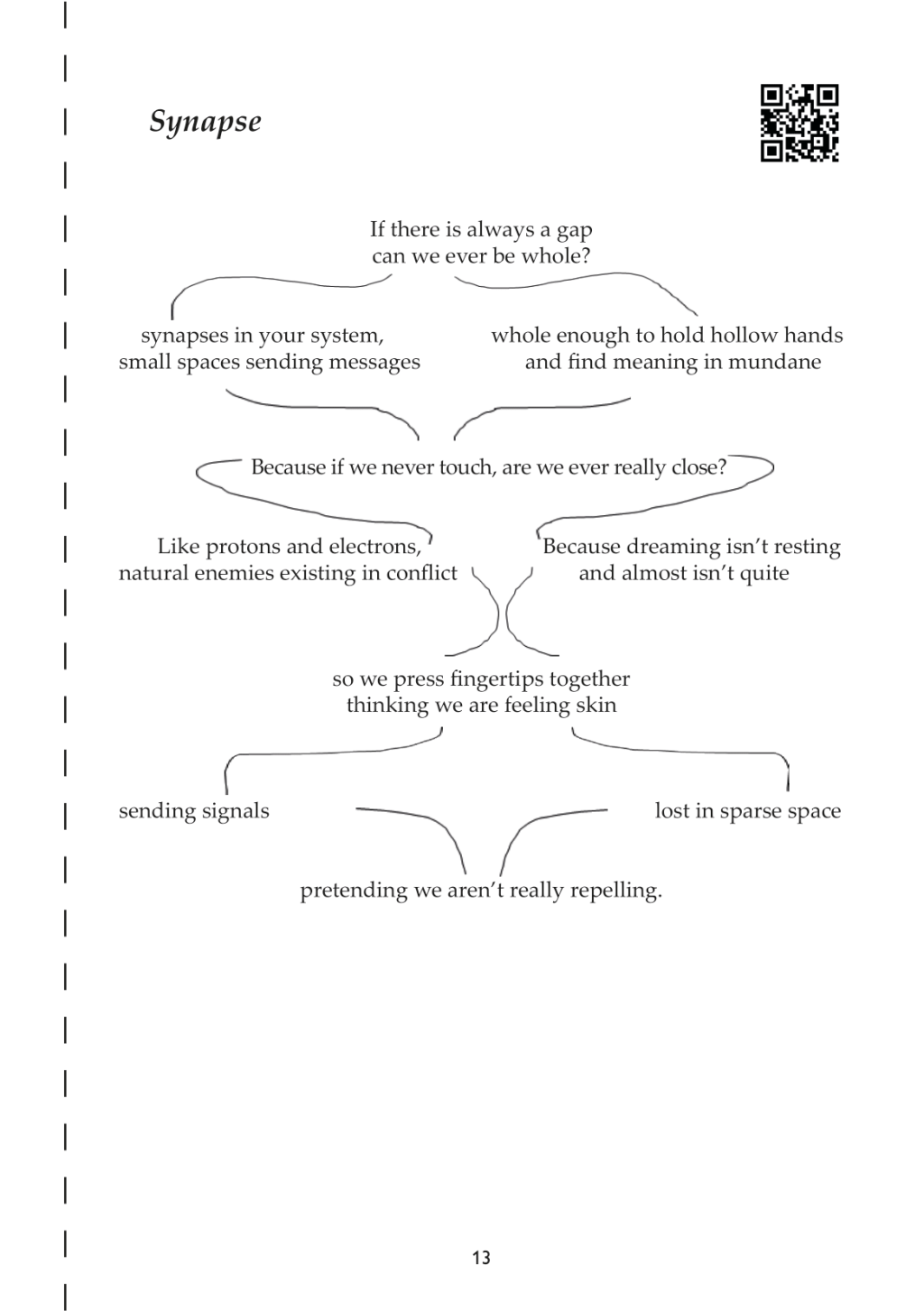

The most interesting use of form is the way different parts of each poem are connected by pen marks on the page. Surely a reflection of the overall theme of connection and separation, this works very differently for different poems. In ‘Pick your path’, for example, the final two stanzas are presented side by side. There are two pen lines leading from the penultimate stanza – one goes to one final stanza, the other to the other. It’s a sort of flowchart poem, where you are given explicit instructions on how to choose between different reading experiences. I think the strongest of these is ‘Synapse’, where the poem veers between two elements: a set of centred stanzas that must all be read, and two sets of stanzas running on either side of them, and you get to choose each time which side you want to read. Reading the left-hand side leaves you with: ‘sending signals // pretending we aren’t really repelling.’ Reading the right-hand side leaves you with the more pessimistic: ‘lost in sparse space // pretending we aren’t really repelling.’

This kind of choose-your-own-adventure style is interesting, because it explicitly nudges us to approach the page in a different way. Perhaps the most dynamic example of this is ‘Dot to Dot’, where different stanzas are numbered one to seven, and connectors link them together so you find yourself reading the page in an unconventional order. It’s a shame that it reads somewhat simplistically next to Astra Papachristodoulou’s ambitious Constellations sequence, but perhaps the way to think of it is that Constellations looks across the whole career and life and scale of a single artist, all wrapped up in a glittery hardback, while Tear and Share gives us something more raw, with more of a punk aesthetic.

To go back to my initial analogy of whether a book chooses to hold your hand or push you out the window, perhaps I should clarify that I don’t mean in terms of whether the work itself is inherently more straightforward or challenging, but in the way the work negotiates a relationship with the reader. For example, many poets prefer the poem to do all the work and find accompanying notes unnecessary. My personal belief is that it depends on the poem. A little context never hurt anyone, especially when looking at unconventional work, and it can make all the difference for a reader between feeling confused or engaged (though shock remains a valid tactic, of course). Which brings me onto The Book of Penteract, an anthology of innovative and largely visual poetry from Penteract Press, with 45 contributors who include Christian Bök, S J Fowler, Philip Terry and (coincidentally) Astra Papachristodoulou. There are notes to the poems too, meaning it pulls you out the window but holds onto your hand, Superman-style, as you take off into the clouds together.

Penteract Press publishes formal poetry, focusing on – as their mission statement says: ‘the structural properties of poetry – in particular, the relationship between content and form. To this end, we aim to promote innovative constrained and visual poetry, as well as works that explore new uses of traditional verse forms.’ It’s worth noting, I think, that the tired-out word ‘experimental’ is not used. And it’s true that when ways of creating poems become more widespread, ‘experimental’ is no longer a valid descriptor. Innovation is everything – taking what exists and finding ways to make it new.

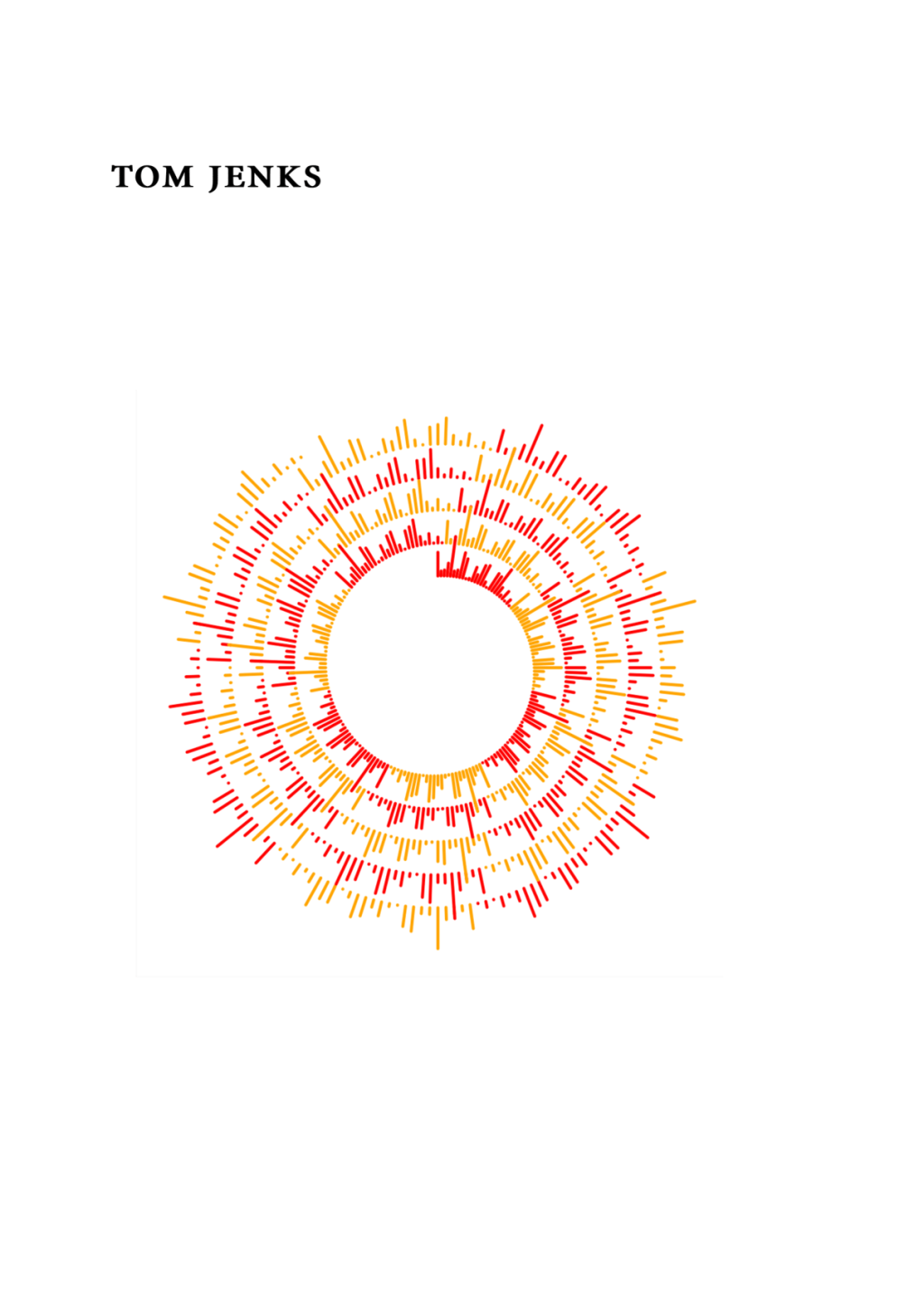

The vast majority of pieces in the anthology are given some context by their creators, all of which I find illuminating. For example, Tom Jenks’s three poems are each visual pieces, one page apiece, and each looks like a very long, thin bar chart turned into a spiral. They are intriguing and satisfyingly measured on the page, but it’s only when I turn to the note that I’m able to get an additional layer of meaning beyond the purely visual. He describes them as visual translations ‘where I programmatically analyse textual structure and express that graphically’. These three images represent Dante’s Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso, with different bars showing the number of letters A-Z present in each Canto, and colour changes indicating the switch to the next Canto. As Tom’s note continues, ‘I could plug in any digitised text and quickly produce results, but there has to be a relationship between form and content. Here, it’s Dante’s vision of hell as a series of circles and the theme of a long, slowly unfurling journey through the afterlife.’ He also sagely notes that while such a project might sound ‘arid and abstract’, for him ‘it’s a fascinating process, exploring my love of colour, shape and pattern, allowing me to work within the lineage of visual poetry in a modern way.’ It’s this level of detail that opens up the work more effectively to the reader, asks them to (for example) consider the alphabetical makeup of hell, and lets them experience the work’s scope and possibility more fully.

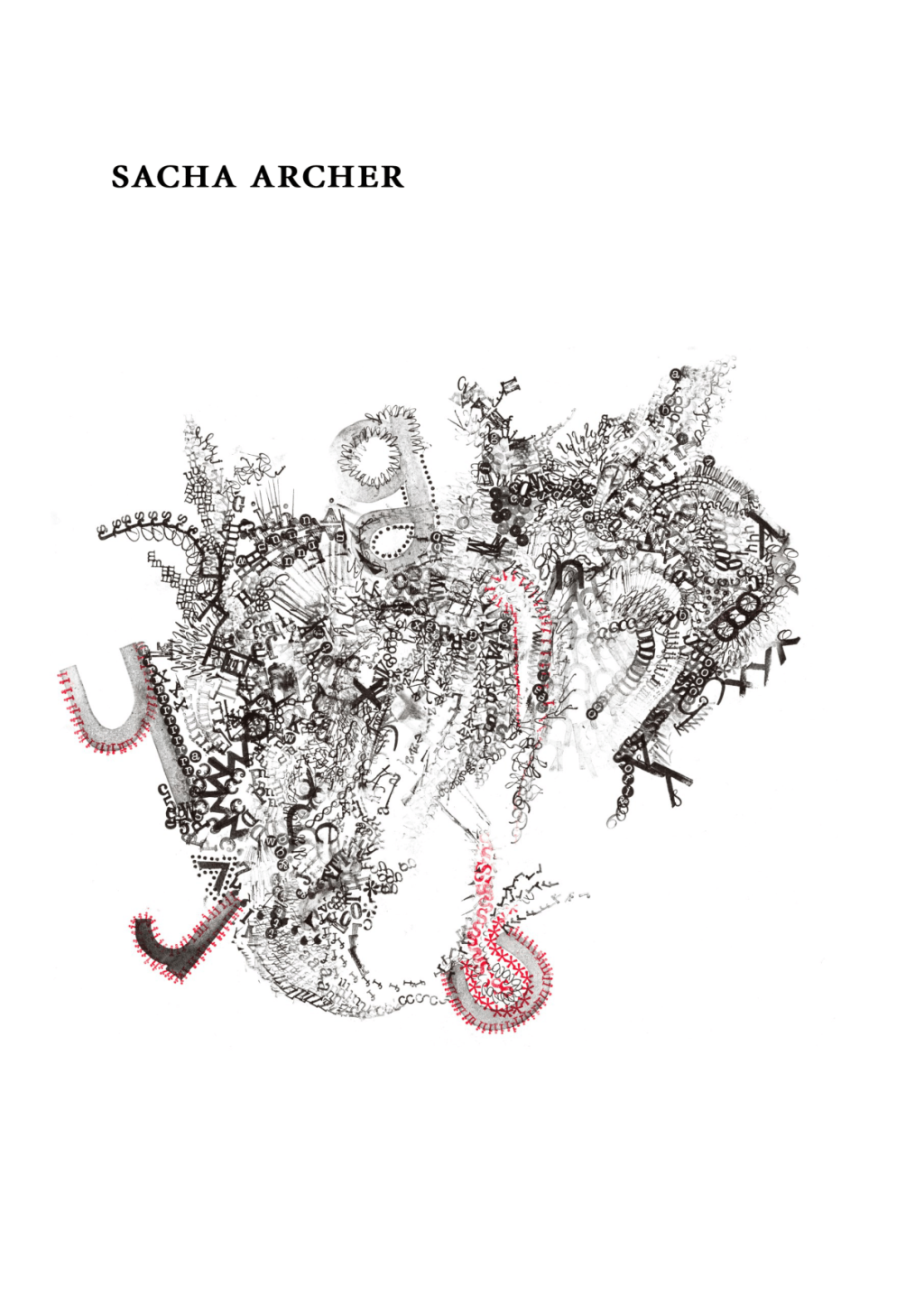

Other effective pieces include Gregory Betts’s typographical responses to the Narsinh font and Sacha Archer’s rubber stamp poems, both of which remind us of the fundamental beautiful instability of the page, not to mention the words, letters, and even fonts we use to try and articulate thought. If poetry aims to nurture a reader’s relationship with the capabilities of language, it’s vital that the way in which language is put together is explored as well.

It’s hard to pick out only a few poems though, as the range of work in the anthology is a dizzying delight, well curated to show off the variety of forms within. You will find emoji translations of Beatrix Potter, the Pope ordering deep-pan pizzas, iambic pentameter intersected by iambic monometer, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ as a crossword rebus, poems that teach you to read them in several different ways simultaneously, lipograms, poetry graphs and games of all sorts, original art, photography, collage and so much more. Rather than removing the authority of the author, this anthology foregrounds the poets’ intentions and explicit attention to form – a choice that will surely serve to demystify and further promote such interesting work.

Chrissy Williams’s collections are BEAR (Bloodaxe, 2017) and LOW (Bloodaxe, 2021). She edits the online poetry journal PERVERSE.