Reclaiming Desire

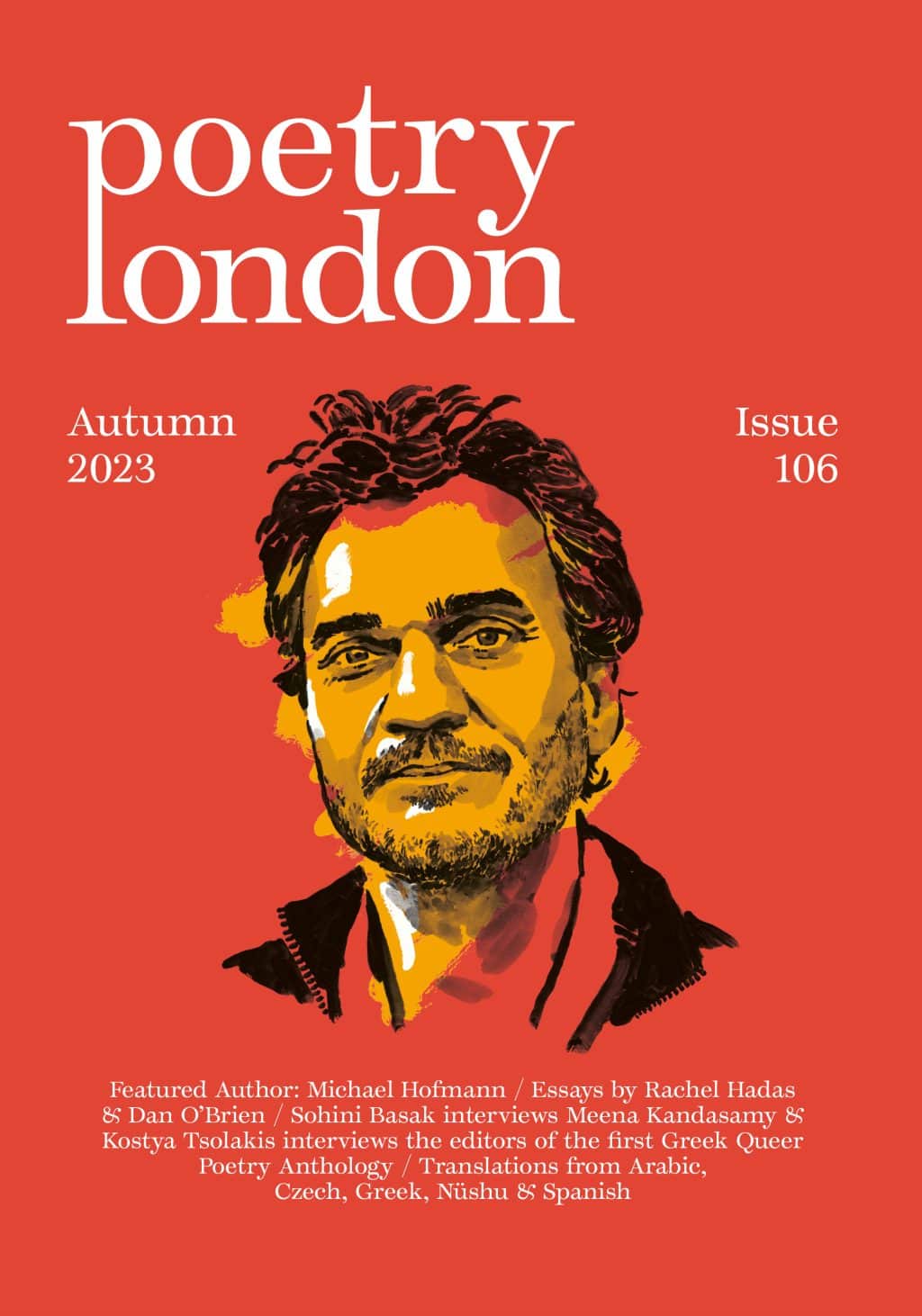

Sohini Basak interviews Meena Kandasamy

Sohini Basak

Meena Kandasamy is a poet, novelist, activist, and translator from Chennai, India. Her writing aims to deconstruct trauma and violence, while spotlighting the militant resistance against caste, gender, and ethnic oppressions. She is the author of the poetry collections Touch (2006) and Ms. Militancy (2010), as well as three novels, The Gypsy Goddess (2014), When I Hit You (2017), and Exquisite Cadavers (2019), which have been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize, and the Hindu Lit Prize. Following the release of Kandasamy’s latest book of translation, The Book of Desire (Galley Beggar, 2023), and in the lead-up to her third poetry collection, Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You (forthcoming with Atlantic Books), poet and editor Sohini Basak met with Kandasamy to discuss the politics of translation and the lexicality of love.

Sohini Basak: The Book of Desire is a translation of ‘Kāmattu-p-pāl’, a 2,000-year-old song of female love and desire, and the third part of the Tirukkural, an epic Tamil text. It is also dedicated to your father, Dr Kandasamy, who made you learn every single kural by rote when you were very young. How did your relationship with the text evolve from those early days to the point where you decided to translate the poems?

Meena Kandasamy: It happened in stages. I got a chance to read the kurals as a teenager because of my father. I was going to a school, a Kendriya Vidyalaya, where I was being taught Hindi and English. Tamil was not part of my syllabus and I was only speaking the language with my parents at home. My dad (a professor of Tamil), who doesn’t speak any other language, introduced me to the text and that was the starting point of an important cultural transmission. Of course, at the time I had no idea that I would one day translate the text. A few years down the line, in my late teens and early twenties, I fell in love, and I remember texting kurals to my boyfriend. He was a much older man, but Tamil and well-read, and I wanted to say something about being in love privately and pretending to be strangers in public. There aren’t enough poems for those kinds of situations, so I turned to a kural. I remember texting him one time when he had not written to me in a week, and my sentiment was captured in a kural, the essence of which was: the person who does not receive even one word of love from the person they love is the strongest-hearted in the world. The poems became a gloss or a shorthand for me to communicate what I found difficult to phrase.

Then, in 2010 I was at a Literature Across Frontiers workshop by Alexandra Büchler. We were a bunch of minority- language poets gathered at Adi Shakti, Pondicherry. There, they encouraged me to translate something from ‘my culture’, and someone suggested I translate some of my Tamil poems. I had to tell them, I don’t represent my culture but the opposite of it, so let me translate from the Tirukkural. And that’s how it started. I kept translating a few kurals every year after that. The idea to make it a whole project began even later, when I started reading the literature around the Tirukurral and I started to register an annoyance with the way the word sex or the discussion around sex had been camouflaged. Sure, some of the words have become archaic, but a lot of that Tamil remains in our everyday currency, so why are we trying to sanitise the text?

SB: What I admire deeply about this book is the way you’ve introduced its context: you take readers through the history of the Tamil language and its script, the centrality of the poet Tiruvalluvar to Tamil culture and imagination, the poetic metre and modes, but also how deeply personal its context is. You write: ‘My Tamilness is where my life as a writer-translator begins’.

MK: Tiruvalluvar survived even after 2,000 years because of how universal and important his messages were. He is a figure that all Tamils can really get behind. We’re a society that’s been trying to reinvent itself – firstly, in opposition to Hindutva, also in opposition to Hindi domination, and simultaneously in opposition to a religious state because India is geared towards a theocratic model. So when as Tamils we constantly try to self-define, Valluvar is one of our self-definitions, in terms of respect, equality, state craft. And he doesn’t attach any one religion to some all- encompassing view of life. The Tirukkural is not a text like, say, the Vedas, which the Brahmins can claim a ‘closer’ access to. No religion nor caste can claim it.

SB: And yet, Tiruvalluvar is being appropriated all the time in the political sphere.

MK: The Tirukkural is being played out in the larger political scene as a Tamil symbol. I mean, Modi has quoted it several times. If you google Tiruvalluvar or search #Tiruvalluvar on Twitter, you’ll come across so many portraits of him wearing saffron and pottu. The BJP is trying to co-opt him in obvious ways, but Tamils are really pushing back on these appropriations, saying he’s not a sanatani, he believes in equality in birth.

SB: Did such political stirrings act as an impulse to put together the translations as a volume?

MK: Yes, but also, no woman has translated Tiruvalluvar. Who is going to do a very flamboyant translation, especially of the third part, ‘Kāmattu-p- pāl’ (literally, the ‘Section on Love’)? The missionary G U Pope, who translated Tiruvalluvar in the late nineteenth century, did not translate this third section, which has always come under scrutiny and has been censored over the decades, because he feared infamy. But I’ve already earned infamy because of my poetry and my politics, and as someone who has always written about sexuality, I’m in that space already. Most importantly, I wanted to liberate this text! Going back to our discussion on Tamil identity, to me it is also about women being sexual, women talking about desire, and women being terrifying – so for me it was: let’s talk about it!

SB: Yes, and you translate against the grain of such blatantly wrongful appropriations.

MK: It’s not only about the recent appropriation, though. As you read and research, you realise that the text was being sanitised even in the twelfth century, for example. There is this classical commentary, one of the most long-standing, by a Brahmin scholar Parimelalhagar where he starts talking about chastity. But Valluvar never said that. And the problem is that a lot of readers came to the text via its commentaries, as they couldn’t access the text (because Tamil is a diglossic language: there is literary Tamil and everyday Tamil; the poetry is written in literary Tamil). So these commentaries became interpretational translations as they were written in standard or colloquial prose.

I realised all the ways in which this text had been twisted: on the religious frontier, the colonial frontier, and also the patriarchal frontier. There are commentaries by Brahmins such as Ramachandran Dikshitar, who compares the text word-for-word with the Bhagwad Gita or the Manusmriti in an effort to Brahmin-fy it, even though these texts are standing in opposition to each other. You have to take it back from them. Or, if we think of what was done to the text in the Victorian period, when Christian missionaries and officers attached to the British Raj tried to highlight the importance of ‘the family’ by framing everything in the third section as ‘chaste wedded love’. But Valluvar is not talking about marriage here. He talks about marriage elsewhere in the book, but this section doesn’t deal with marriage. As a translator, my effort is to take the text away from those kinds of readings. So, to me, decolonising operates not only in the act of translation but by the act of translation.

SB: And that’s what you mean when you say in your introduction: ‘If translation is to be a decolonial practise[sic], it calls for us to widen the scope of what colonialism is, and what it involves.’

MK: Where does the decolonisation come from? If you look at Brahminism or Hinduism or Sanatani culture as an act of colonisation of Tamil people, how did it take place? Now, in Keezadi (in southern Tamil Nadu), there is an ongoing archaeological excavation that has unearthed evidence from 3,200 years ago of people having literacy, people using some form of written culture. How did something like literacy, which was widespread among the people, become so exclusive? It’s a result of caste colonisation, isn’t it? And what did it do? It made education the preserve of the Brahmins. Something that was for everyone became something that was specific to a caste. But worse than that, it denied all education, all thought and all intellectual facilities to women.

So when you write or translate from one location as a woman and another location as a lower-caste woman, you take this

intellectual authority that has been vested on a certain class of people, and then you’re fighting Hindutva and Brahminical colonisation which says that intellectual activity is meant only for the Brahmin male. It’s a very important intervention then, when you’re taking that space from them and saying, I’m a commentator and a cultural activist. It’s important for me to say that I am the Tamil woman and as a Tamil woman I can liberate – via my translation – the Tamil woman who exists within the text from all the layers of hypocrisy under which you have buried her.

SB: You started the first translations in 2010, the book was published in 2023. This year is also important to your own poetry – we’re finally seeing the publication of your third collection Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You, after the explosive Ms Militancy. However, in between you published three novels and other works of prose. What sort of a relationship does your poetry have to your prose?

MK: You’re a poet, so you know we need to find a certain calm, a romantic mood – we need to be in love and all of that. That said, The Book of Desire and Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You are my pandemic babies. During the second lockdown in London, I moved to India with two little children. I was single parenting the kids, and I was beginning to watch in real time my brain become a fossil. My kids would suddenly say the speedy car goes faster than the bicycle, and the choo-choo train goes faster than the speedy car. I realised that while I couldn’t write a novel with the kind of attention I had to give to my children, I could work in bits and patches, in fragments of time. And so, I would sit with a 2,000-year-old kural that has seven metrics in Tamil and process it word by word, its lexical

and purported meaning.

SB: Perhaps because I read Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You right after reading The Book of Desire, I see Tomorrow as a collection of love poems to friends, comrades, political prisoners, to writing and reading – and yet violence seeps into the poems very quickly. Would you like to talk about that?

MK: Something happened after the publication of Ms Militancy in 2010. There are some books that become bigger than you. And it’s not about selling a million copies, or in my case it’s not the publisher’s marketing mechanism (it was published by a small press); I started to feel divorced from the success of the book. It had turned into an accessory for young women, a stand-in for being cool or feminist. Poems from the book were also part of university syllabi. The criticism around the book was savage, I got called ‘ultra-feminist’ and so on.

If you’re a communist, you’re against that sort of branding. Anyway, I was still in my twenties, and I thought: do I want to be this angry female poet all my life? What will I do at the age of fifty? It seemed very tied to an expiration date. On the other hand, it’s perhaps a personal obsession given my social location – I’ve always wanted to take up space where women are not usually allowed to take up space, so I then went on to write a lot of political essays and work on novels.

The only time I wrote poetry in those days was when something terrible happened and I could only respond through poems. After the Delhi gang rape, an editor commissioned me to write a poem. I turned to poetry when my friend got arrested, and after the Hathras rape. Then COVID happened. And a poem on not writing poems emerged in the wake of the lynching of Mohammad Haqlaq. Even though I was not writing poetry regularly or actively, I realised that perhaps because of the specific moment we live in, poetry became the most effective way to say what we have to say. So I would say that the book is much more of a political project than a love project, except that the political poetry took the shape of love poetry, and since my partner himself is an activist, there was some of that. I think one tends to fall in love with political people, and then the act of falling in love becomes political.

SB: We spoke of Thiruvalluvar as the figure of the poet. What do you make of the figure of the contemporary poet in India?

MK: I don’t think poets are trivial at all. There is clearly an opposition to poetry and a pushback against reading by the regime. In fact, there have been protests against my work being taught at universities, so clearly, poetry is important enough to cause this kind of censorship. Then there are those poets who are being jailed. What’s interesting to me – if you want to talk about the ‘figure of the poet’ – is that none of us are on our own. We are a community at the heart of it all; I don’t exist alone, I exist also as the editor of Varavara Rao’s poetry translated into English, or as someone who can push for the prison writings and poems of G N Saibaba to be published. So, you don’t exist only for yourself, you also exist to make the voices of those under threat or in prison heard.

Sohini Basak is a writer of fiction, poetry, and the in-between. Her first poetry collection We Live in the Newness of Small Differences was awarded the inaugural International Beverly Manuscript Prize and published in 2018.