Open Surfaces: Sohini Basak talks to Ursula Andkjær Olsen and her English-language translator Katrine Øgaard Jensen about their multilingual practice

Sohini Basak

Sohini Basak: Ever since the pandemic broke out, I’ve so often come face to face with the inadequacy of words while grieving or trying to console a loved one. In that context, thank you so much for writing Outgoing Vessel, Ursula, and for making it available in English, Katrine, because even as a non-religious person, I was struck with a rare sense of clarity on reading the section of the book titled ‘the precision of a prayer’. It begins with: ‘prayer as talking sense to yourself / as starting in one place and ending in another’.

I wanted to start our interview on that note, Ursula, since you write from a deep place of loss and grief, and the raw wounds of anger, frustration, self-hatred and helplessness that come in their wake: if you could articulate for us how your practice has evolved from a seemingly wordless and even existential place of feeling, and how you are able to anchor yourself with words?

Ursula Andkjær Olsen: First of all, thank you, Sohini, for inviting us to this conversation! I first heard of the idea of prayer as talking sense to oneself at a talk on Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish existentialist philosopher. I’m not sure whether Kierkegaard wrote those exact words or if it was the speaker’s words, but I grabbed on to that line, because it made so much sense. And I had it working in me for some time, until this idea of the ‘precision’ came up. I’m not a member of any religious community either, but I’ve always been praying. Since I was a kid. It’s a very important form of communication, I think – because it’s assuming that there is someone to turn to even when there isn’t, and even when there are no words, nothing to say. Or maybe simply somewhere to turn. Even when you are alone. That turn is the important thing. I think that the turn is important for language as such because it builds in a listener. Who is not there, yet always there – before you say anything or have anything to say at all. You can talk to yourself, or just listen to yourself (or maybe ‘yourself’ is not at all the appropriate expression…), and if you listen carefully enough – with precision and not just in dualistic terms of good–bad, up–down (or in ‘monistic’ terms of bad and down!) and so on – something will happen. The dualism and/or ‘monism’ will be interrupted by something else. It is not like you’ll end up in a completely dead loop. Something will change, move. That listening is what happens in that chapter. In the beginning the ‘talking sense’ is NOT an option, there is no going from one place and ending up in another. But in the loop, things happen. Maybe the anchoring element is not the words (nor in the words) but the turn – the ‘turnedness’. That there is a loop, a circuit, a chain. Hope is an error, a glitch in this seemingly dead loop. Maybe? This is a question.

SB: Katrine, if you could add to that, because translation in a sense can be seen as ‘starting in one place and ending in another’, but so much goes on in between those two points, perhaps especially while translating a book of poetry as intimate, powerful and vulnerable as Outgoing Vessel.

Katrine Øgaard Jensen: Absolutely. When I first started translating this book, my world in New York City was somewhat ‘normal’. By the end, I had suddenly lost my father to cancer and we were in the middle of a global pandemic during which New York City, one of the early hotspots of COVID-19, had completely transformed. I was filled with grief, but also a lot of rage, and this anger unlocked the task of translating Outgoing Vessel for me in many ways. Translating Ursula’s words became therapeutic because I felt like I could scream every line onto the page. It gave my anger and grief an outlet, while simultaneously channelling the anger and grief of the book’s speaker. I like that you describe Outgoing Vessel as intimate, powerful, and vulnerable, because those words pretty much summarise my experience of translating the book.

SB: In the book’s translator’s note, Katrine writes: ‘According to Olsen, she is simply the first translator of the idea, and I am the second.’ I’d love you both to elaborate on this in relation to this book, which as we also find out from the note, features several ‘technoscientific poems’ which were created by the poet by ‘running the text through multiple languages in Google Translate’. Truly fascinating! So, the book we receive as English language readers, is a highly complex palimpsest that challenges linguistic hierarchies, right?

UAO: The short answer: yes! The question of who is actually talking is up in the air – there may be no one to listen, but there might also be no one to do the talking/praying. To connect to the loops we were just talking about.

KOJ: Yes, especially when it comes to the technoscientific poems that you mention. When I asked Ursula how these poems originally came about, she shared with me that the first poems she wrote for Udgående fartøj (Outgoing Vessel) came out hammer-like, hard and mute, unable to really say anything. That’s why she started Google translating the poems she had written: to bring some softness into the work. So, you have this hard human that becomes, ultimately, incapable of expressing itself, but then this machine emerges and suddenly adds a searching quality, some life and fragility to the texts. As if to say that there is a softness behind it all, after all. Open surfaces like the touch screen / looking glass seem to provide an alternative option or mode of being for the hard, closed human — a shift expressed by the speaker in one of the last sections of the book titled TECHNOSCIENTIFICSALVATION:

my goal is to invalidate ALL loneliness my goal is to communicate WITH EVERYTHING i launch the orb as an outgoing/incoming vessel i have slowly begun to break out of my isolation the inhuman is not unfriendly i have started working on my softer parts i have started communicating through body expansions touch screen looking glass touch screen looking glass /orb

This is, however, a very orderly poem compared to the actual unravelling of language that takes place in the technoscientific poems at the end of each section. In the case of the technoscientific pieces, I, the translator, was the hard human. In order to translate these chaotic poems, I had to open up to the possibilities of the machine and resist my urge to create order, my urge to ruin the open-ended lines by closing them with my human hardness and logic. At the same time, I knew that if I just translated the technoscientific poems directly into English without the filter of a literary translator, they would not read as cut-up poetry arranged by Ursula. My only option, then, was to become a cyborg poet-translator and try to channel or intuit the open possibilities of a machine while also arranging words and lines in aesthetically pleasing sequences.

I like what you say about challenging linguistic hierarchies – that’s an interesting way of looking at Outgoing Vessel as a writing and translation project. The collaboration between human and machine certainly challenges ideas of authorship, originality, mastery, as does my collaboration with Ursula in general. Who wrote what? Are you, the reader, reading lines that Ursula wrote, or did a multilingual neural machine translation service write them, or did I write them? I like that I’m unable to answer this myself. It’s like everyone and no one wrote these poems.

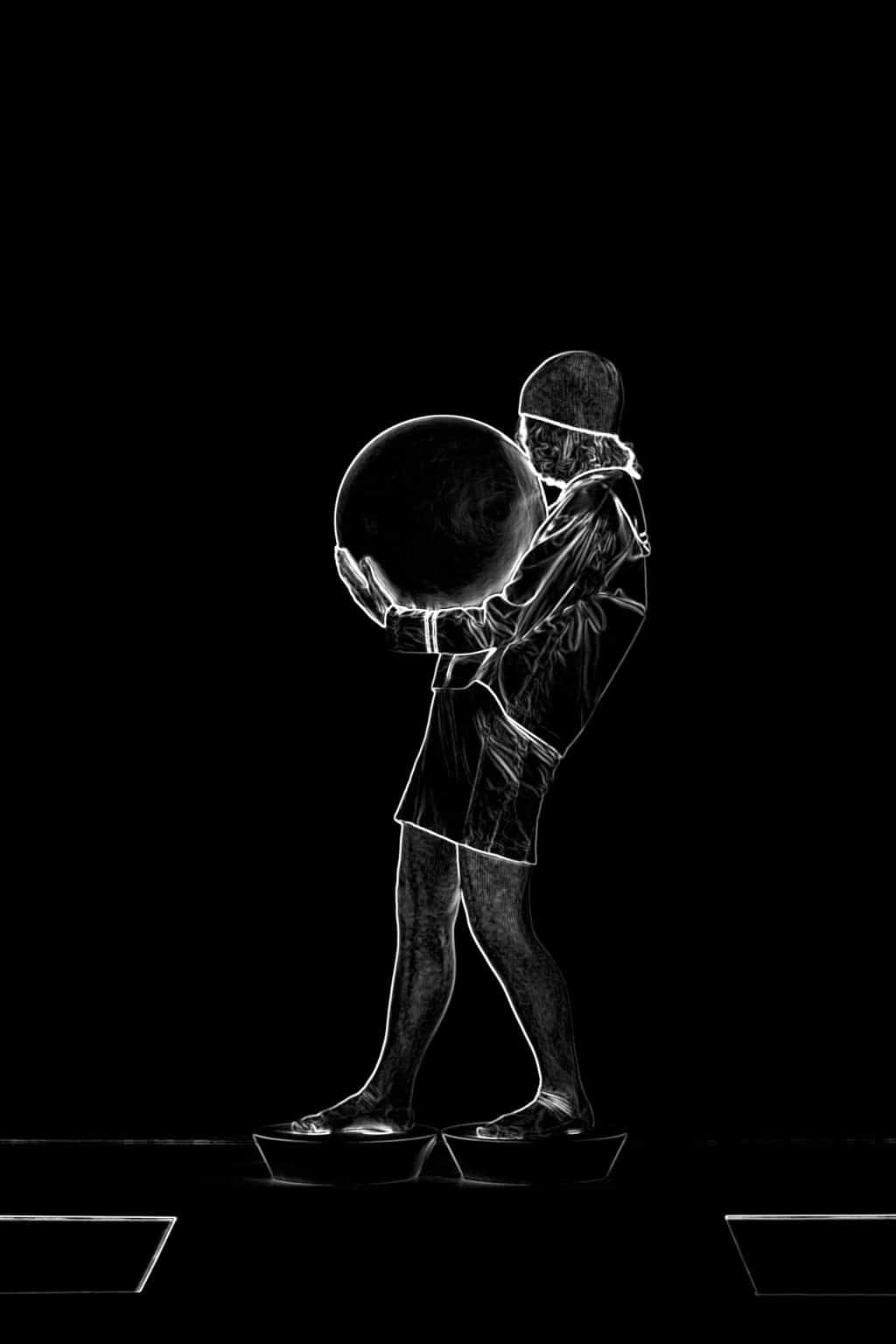

SB: As in Ursula’s book-length poem Third-Millennium Heart, the body, or more precisely the mother’s body and its relation to a mechanised and mercantile world is at the heart of Outgoing Vessel. In this book, you add to that relation ‘an infinite loop’ of feelings in the central image of an orb – the ‘outgoing vessel’. ‘Inside me there is a nondegradable orb / my own planet’ – how did you fix on the orb as the main vessel?

UAJ: The orb, yes. Well. I think the root of this imagery is an intuition. The intuitive answer to the question: where to hide stuff (or yourself) the best. I was in a very bad place, when writing this book, a place where I felt an intense need for protection, and, also, I needed ways of shutting down feelings. The orb is that kind of geometrical body that has the ‘safest’ core. From the centre there is the exact same distance to every point on the surface – meaning: there are no weak spots. Paranoia’s best friend! To travel safely you will need an orb. Also, if you need to contain something deadly – something poisonous, nuclear waste for instance – you might go with an orb. In my opinion.

After this first intuition the images came along: the pearl, the (pregnant) uterus, the egg (or some kinds of eggs, at least), the diving bell (from cartoons). From another direction the Danish sculptor Sophia Kalkau’s work with pure geometric forms inspired me. She made the beautiful cover and the photographic series in Outgoing Vessel. Cranach’s Melancholia was another important influence. In that painting there is an orb – I think normally meant to represent the world, earth, infinity, perfection, stuff like that – but for me this orb became the exact image of melancholy itself, the blob of lead-heavy black bile in a vacuum.

SB: Tell us about the decision to include the photographs by Sophia Kalkau. How did this collaboration come about and at what stage of the composition?

UOA: Sophia and I have been working together for quite some time, and maybe more importantly, we have been following each other’s work for almost twenty years now. I’ve been writing texts for her works (for exhibitions, their catalogues), and she has made covers, lay-out and art works for several my books. It is not that we ‘work together’ – we are not poking our noses in each other’s choices, you know. She is doing her work, and I’m doing mine, but we are inspired by each other, and it’s really like we can complete each other’s work. At least Sophia’s work with my books is adding something that for me seems like a fulfilment. To me the photos deepen the experience, or deepen the space in which the experience is meant to take place.

The photographic series for Outgoing Vessel was made after the manuscript was finished – or at least in the finishing stages. She got the manuscript, she read it, maybe a couple of times, and then she made the series and the cover. And after that the layout.

SB: The lines ‘my goal is to invalidate ALL loneliness / my goal is to communicate WITH EVERYTHING’ have stayed with me. The book-length poem, too, communicates with everything: philosophy, philology, hybrid religious hymns, sci-fi hyperdreams, planetary warnings, and so on… When you make your art, do you think about genres as such or are you always drawn to crossing boundaries between genres to paint a bigger picture?

UAO: The short answer is yes – the second option! To me genres and the boundaries between them are simply not in scope, in focus. I don’t think about them very much. Technically and formalistically (is that the right term?) you can do anything when you are writing, and for me poetry is that freedom.

SB: Katrine, as in the previous book, you have made a point about the deliberate mistranslation of certain Danish words, especially neologisms and compound words. Could you tell us more about such choices in Outgoing Vessel?

KOJ: It’s interesting, because when I first started translating Ursula’s work, I didn’t really think about what I was doing as part of a specific translation strategy. I just translated lines and images in ways that sounded interesting to me in English. When Third-Millennium Heart came out, I kind of held my breath because I was worried that literary critics or readers would think that these ‘mistranslation’ choices were a result of my translating into my second language. I felt that I was running a huge risk of being labelled as a bad translator. It wasn’t really until I read Johannes Göransson’s essay collection Transgressive Circulation (Noemi Press, 2018) that I believed there was some legitimacy to my translation practice, or at least that I wasn’t alone in my wish to create small monsters out of the meeting between languages. In my translator’s note to Outgoing Vessel, I mention some examples of how I wanted to let Outgoing Vessel mutate in translation and give it its own expression in English. Instead of translating forvredethed as ‘distortion’ or ‘twistedness’, for instance, I decided on ‘wrungness’. In another poem, I chose to directly mistranslate the Danish word ‘skamrides’ to ‘shameridden’ instead of accurately translating the word to ‘overridden’. I did this to preserve the play on shame in the Danish lines ‘jeg er et æsel som skal skamrides / jeg er et dyr som skal elskes skamløst af de skamløse’, which in the English translation became ‘i am a donkey that must be shameridden / i am an animal that must be loved shamelessly / by the shameless’.

Working with poetry in translation is most rewarding to me – as a writer and a reader – when there’s room for an exchange between languages that results in the renewal of the target language. I read poetry to rewire how I think about form and language, and I want poetry in translation to do the same. To me, one of the worst things a translator can do is ‘iron out’ a poem in translation in order to create a smooth and pretty poem in English without any of the subtle strangeness that made the original interesting in the first place.

SB: If I could come back to the endless anxiety and collective grief of these times, what are some practices or works of art that have kept you both afloat during the pandemic months? And have you been able to work on new projects? If it’s possible, we’d love to know what we can expect from you both next.

UAO: I’ve been reading a lot of great stuff. Last year the wild and violent poetry of Enheduanna – the first known poet – was translated into Danish. Amazing! This winter two different translations into Danish of all Sappho’s fragments came out. Right now, I’m reading the American classicist Page duBois’ Sappho Is Burning. Last year I read her book Amazons and Centaurs, she’s so great. I’ve also been reading Greek tragedies – and Canadian-American political theorist Bonnie Honig’s book on Antigone, Antigone Interrupted. A very important book, I think. Also new(er) works, of course, Claudia Rankine’s latest, Virgin-Island novelist and poet Tiphanie Yanique’s Wife, and works by Australian xenopoet Amy Ireland. Wow. Also, I’m looking forward to the first book in Danish of Angolan poet Aaiún Nin this fall.

Here in Denmark the lockdowns were not as heavy as in a lot of other places around the world. At the same time, I am headmaster of The Danish Academy for Creative Writing, so I’ve been extremely busy during the last one and a half years, constantly re-planning, re-scheduling, re-thinking our semester programs and so on. For me the work stress – luckily – was more evident than feelings of depression and isolation. I have had so much to do that I haven’t had the time to really sink into the situation. Another very important thing: my economic situation has been secure. A lot of people – also a lot of my fellow writers and artists in general – have had an extremely hard time just getting along.

Because of the work craziness I haven’t been writing a lot, and more importantly I don’t really know what it is that I’m writing right now. Or what it is that wants to be written… so I can’t say much about it. But I’ve been working with tarot cards – maybe as a kind of expanded prayer – a space of divinations, predictions, oracles, circuits of past, present and the future, ha ha… listening to the glitches of these not so dead loops. Things that are not there – hope that is (almost) not there – but are at work anyway. There is this story about the Danish scientist Niels Bohr: he had a horseshoe over his door as a lucky charm, and he was once asked if he believed in that kind of superstition. He answered that of course not, but he’d heard that it was working anyway. Sometimes talking sense to yourself also means bypassing sense or rationality.

KOJ: After finishing my translation of Outgoing Vessel in 2020, which was an emotionally freeing but also taxing process, I wanted to turn to lighter modes of writing. I’ve since worked on a series of mistranslations/remixes of Ursula’s poems, some written in response to Outgoing Vessel and others in collaboration with Ursula (an excerpt was recently published in BOMB Magazine). The mistranslations are a bit of a mix between surrealist writing methods and collaborations with online poetry generators and/or physical aids such as magnetic tech words that I got at the Computer History Museum in California. Ursula mentioned tarot cards, which is interesting to me since I have incorporated my own preferred divination practice, rune readings, into some of my mistranslations of her work as well. In this context, I’ve been rereading some of my all-time favorites like CA Conrad’s ‘Quartz Crystal Shakespeare Sonnet Translation’, Sawako Nakayasu’s Mouth: Eats Color, Christina Hawkey’s Ventrakl, and Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony for inspiration. Recent inspirations include Paul Legault’s The Tower – a ‘translation’ of W. B. Yeats’s The Tower – and Paul Cunningham’s The House of the Tree of Sores, a sequence of bilingual prose poems set in a US-based IKEA department store, as well as Baba Badji’s multilingual poetry collection Ghost Letters.

In terms of future translations, I am currently finishing up my English version of Ursula’s latest work, My Jewel Box, which is forthcoming from Action Books in spring 2022. It’s the third book in the trilogy of Third-Millennium Heart/Outgoing Vessel/My Jewel Box, so it will be the end of a translation era for me – although I will still be working on Ursula’s many other past, present, and future books.

Sohini Basak’s debut poetry collection We Live in the Newness of Small Differences received the International Beverly Manuscript Prize and was published in 2018.

Ursula Andkjær Olsen (b. 1970) was born and raised in Copenhagen. She has a degree in musicology and philosophy. Olsen made her literary debut in 2000 and has since published ten collections of poetry as well as a novel and several libretti and dramatic texts. Olsen has received numerous grants and prizes for her work including the Danish Arts Foundation’s Award of Distinction in 2017.

Katrine Øgaard Jensen is a writer and translator from the Danish. In 2018, she was awarded the National Translation Award in Poetry for her translation of Ursula Andkjær Olsen’s book-length poem Third-Millennium Heart