Editorial by André Naffis-Sahely, Issue 99

André Naffis-Sahely

I am a citizen of the world, and therefore, according to some, a citizen of nowhere. Having been forced to leave the United Arab Emirates at the age of eighteen, when I outgrew my status as one of my Iranian father’s dependents on his visa, I arrived in the UK in 2004 and began a degree in history and politics at the University of Leicester. Having grown up among millions of transnational ‘citizens of nowhere’ in the UAE, I knew a little about a lot of countries, and one of the few contemporary British institutions I was aware of was Poetry London. I had chanced across the magazine in one of Abu Dhabi’s only well-stocked bookshops as a teenager in the early 2000s and reading it influenced my decision to study in Britain, and later, to join the ranks of London’s literary community.

Two decades later, as I take up the reins at that magazine, I should be joyful, but I’m not. While assembling the poems for this issue filled me with unqualified hope in our global wealth of talent, imagination and humanity, I prepare to return to a Britain utterly unrecognizable to the country I lived in happily for over a third of my life. This new Britain is smaller, meaner, weaker, angrier, and even worse, unable to effectively focus that anger effectively. The result? A provincial culture unmoored from even its closest neighbours, a gang of public school boys using public power to enrich private corporations, record-high COVID- 19 deaths, and a limp Opposition. Capitalism did that. The monarchy did that. The Conservative party did that. Brexit did that. The people did that. The latter might be toughest to stomach.

It would be easy for me to sit here and pretend that none of this has anything to do with a literary magazine, least of all a poetry magazine. The fact is that the UK’s literary culture lies in just as deplorable a state as the rest of the country, and why wouldn’t it be? It’s not a pretty picture: literary sections in newspapers have disappeared, forcing writers to produce ‘content’ for Health or Entertainment sections, corporate publishing monopolies are busy suffocating a dwindling market, talent is too neatly herded into the world of workshops and academies, and literary prizes are breeding grounds for nepotism, slavishly devoted to fashions rather than to artistic merit.

Nevertheless, owing to the fact that some writers of colour, or anyone deemed to be an ‘other’, have gained more prominence, we hear some toothless old wolves raise their voices to grumble that ‘we’ve gone too far’, that literature and freedom of speech are now enslaved to notions of ‘wokeness’ determined by the élite and that the literature of today is an insult to the literature of the past. Is that really what’s going on? What I see is altogether different. The establishment picks one or two individuals from each disenfranchised community and then hands these spokespoets a restricted selection of the kingdom’s keys, enlisting the names of these artists in their campaign to preserve the power of a still mostly white, mostly wealthy élite. They assemble the illusion of diversity like one would order a balanced meal off a menu. They call this the ‘woke’ revolution.

The literary establishment’s hollow embrace of diversity and its systematic corruption are not solely defined by notions of diversity. The rot reaches all levels of absurdity, creating situations where organizations can happily hand out awards to artists for fighting for ‘freedom of speech’ using grants from corporations like Amazon, who seem able to tolerate people speaking their minds, except in the workplace, of course, since they threaten and harass anyone who does so in their warehouses.

What happened? What I do know is that it didn’t have to be this way. Sincere reforms and actual power-sharing might have led to a genuinely diverse and challenging literary scene, arguably a vital component of any healthy society. Instead, what we have is a so-called ‘culture war’ à l’Américaine, with both ends of the political and cultural spectrum basing many of their actions and stances on mentalities shaped entirely within echo chambers, divorced from pondering real concerns and achieving real change. Meanwhile, so many leading lights who should be speaking out about all this wind up falling over themselves in their quest to scrape and grovel for an OBE.

Poetry London’s artistic vision going forwards is based on the understanding that change is not polite and neither is it ordained by a single individual, or interest group. Change is argumentative and talkative and challenging and uninhibited and this magazine will seek to do all it can to encourage that sort of thinking and be a home to it. Poetry London was founded in 1988 at the height of Margaret Thatcher’s power, the initial laboratory for the conservative Austerity of the 2010s, and its roots are punk and DIY, born as a listings magazine, it sought to provide an alternative to the Oxbridge circle-jerk that once ruled the literary establishment, and in many ways still does.

Honouring those origins, we will publish poems that shock and unsettle. These poems will speak of trauma, war and injustice, because that is the world we live in. We will prioritize work that deals with issues of migration, economic injustice and freedom of speech, introducing our audiences to poetry of the highest level that also addresses the most pressing issues of our times. There is also much that we won’t do. We will not assist in creating a new élite of writers just as unanswerable and privileged as their predecessors, we will not seek to promote spokespoets when there are entire creative communities to be considered beyond what is deemed to be popular on Twitter or Instagram, and, hearing our colleagues from more disadvantaged backgrounds, we will work to help our fellow artists achieve positions of power and influence, thanks to a new editorial training scheme currently being established. Discussing change inevitably leads one to want to see that change actually take place. Obviously, we can’t do it alone, but we aim to do our part. We hope others will join us and we’ve no doubt they will. Something must be done.

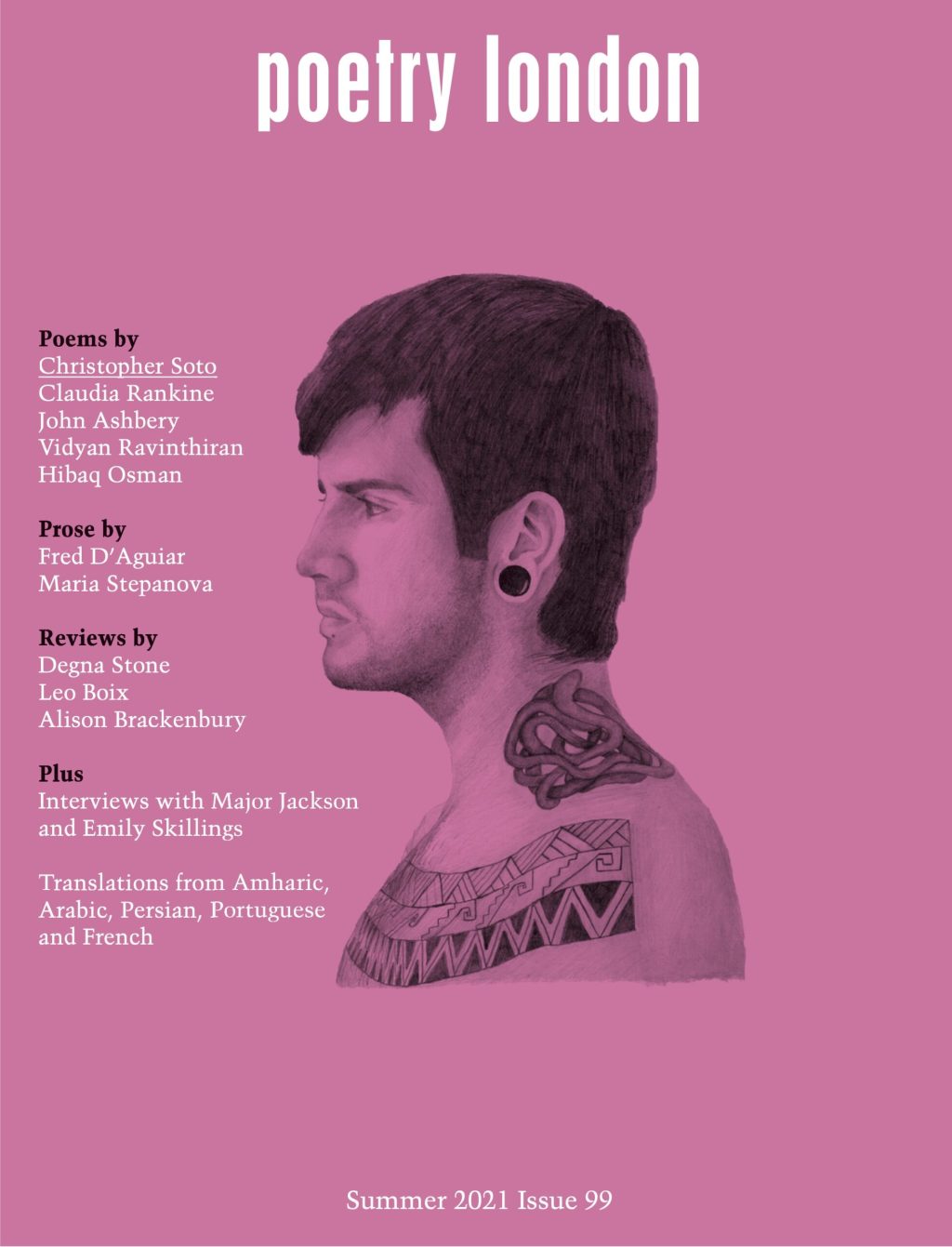

I believe that the writers presented within this issue’s covers are passionately committed to what it means to be an artist and to seriously engage with one’s world. Many of them are activists and teachers, all necessary voices. The issue’s centerpiece, ‘Then A Hammer // Realized Its Life Purpose’, is written by Christopher Soto, whose family migrated to the United States from El Salvador, and who is a poet, novelist and co-founder of Undocupoets, which works to support undocumented writers in the US. Soto’s stylistically inventive, painful memoir of abuse within his childhood home – ‘this is the story of hands on us’ – may prove difficult at times, especially to anyone who might have suffered domestic violence, as so many more have done during this pandemic, yet the author’s wry humour, understated wisdom and lyrical mastery make this an essential poem to read. Also featured in this issue are poems by Anne Waldman, Claudia Rankine, and a previously uncollected poem by John Ashbery (1927–2017), a preview of the wonders to come in Parallel Movement of the Hands: Five Unfinished Longer Works by John Ashbery (Carcanet, 2021). The book’s editor, American poet Emily Skillings, is interviewed in this issue by our Reviews Editor, Dai George.

Other highlights include Vidyan Ravinthiran’s elegy to the murdered Sri Lankan journalist, politician and human rights activist Lasantha Wickrematunge (1958–2009), an excerpt from an epic poem entitled ‘MDVL: 1,000 Years of Dark Ages’ by Adam Green, anti-folk singer-songwriter and former half of the band The Moldy Peaches, a poem by Kevin Opstedal, California’s ‘surf noir poet’, whose work always evokes the Golden State’s oceanic views and rocky coasts, and the work of younger poets such as Momtaza Mehri, Hibaq Osman, Sarah Lasoye, Taher Adel, Roseanne Watt and Seán Hewitt. This issue reaffirms Poetry London’s long-standing commitment to internationalism and it includes work originally composed in Amharic, Arabic, French, Persian and Portuguese, namely poems by the Palestinian poets Najwan Darwish and Olivia Elias, as translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, the Brazilian poet Ana Cristina Cesar (1952–1983), as translated by Elisa Wouk Almino, the Iranian poet Fatemeh Shams, as translated by Armen Davoudian, the Egyptian poet Iman Mersal, as translated by Robyn Creswell, and the Ethiopian poet Meron Berhanu, as translated by the author and Nardos Mekuria.

I am especially grateful to the authors and publishers of PL99’s featured essays, which are excerpted from what I believe to be the finest nonfiction books of 2021. The first featured essay is an excerpt from Fred D’Aguiar forthcoming Year of Plagues: A 2020 Memoir (HarperCollins, 2021) which discusses his Caribbean upbringing and his American lifestyle amidst his battle against cancer, the pandemic and the fight for racial justice in America, and this excerpt pays special attention to the murder of George Floyd. The second featured essay is taken from Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021), a multifaceted chronicle of a Jewish family’s life in the Soviet Union and Russia during our age of extremes, as translated by the inimitable Sasha Dugdale, who eight years ago entrusted Poetry London with the publication of Stepanova’s first poem in the UK, of which we are immensely proud.

A city as great as London belongs not just to England, or Britain, or Europe, but to the whole world. Poetry London understands that. In that spirit, we mourn the brilliant lights lost to us over the course of these terrible two years: Eavan Boland, Kamau Brathwaite, Miguel Algarín, Lewis Warsh, Diane di Prima, Derek Mahon, Michael McClure, Salah Stétié, Ernesto Cardenal, Anne Stevenson, Jalal Malaksha, John Pepper Clark, Colin Falck, Lewis MacAdams and Adam Zagajewski. They were all cosmopolitans and they also knew that people throughout history have always hated individuals who feel at home everywhere.