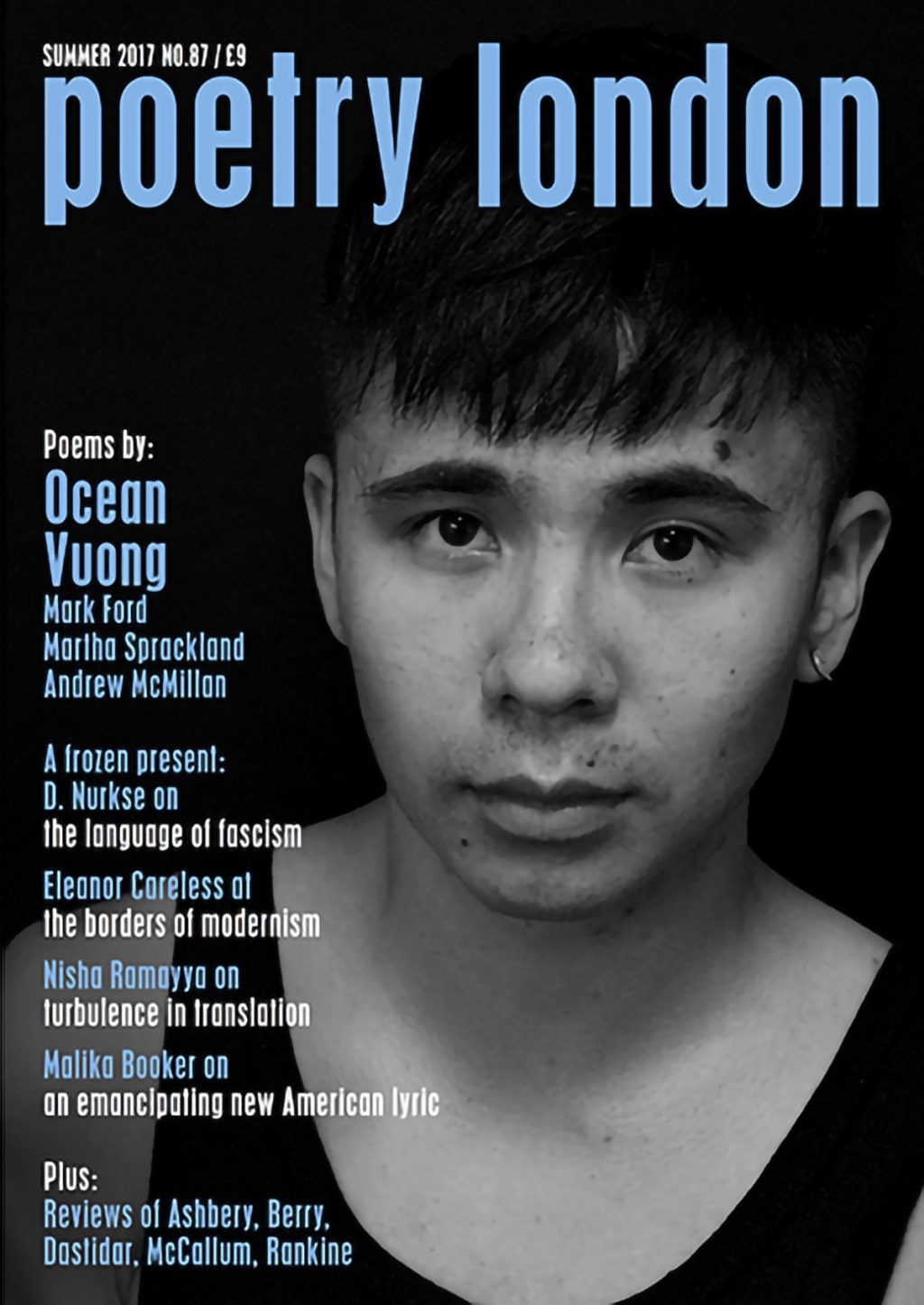

Poetry as Artifact and Historical Testimony: Malika Booker on an emancipating new lyric

Olio

Tyehimba Jess

Wave $25

Tyehimba Jess’s second collection Olio is a beautiful rendering of minstrel performers post-slavery. Jess and Wave Books have deliberately cultivated a coffee-table art book effect in which the book’s scale, typography and illustrations are woven into its poetics.

Jess writes into the African-American poetics of the kind poet Frank X Walker terms ‘A Historical Poetry […] committed to historical truth, arts activism and paying tribute to our ancestors’. Olio is therefore in conversation with and follows Walker, alongside other poets like Elizabeth Alexander, Adrian Matejka and Robin Coste Lewis, whose work is preoccupied with a factual restoration that re-positions and centralises black voices in the American landscape. These poets merge archival records with pseudo-autobiographical poems to create a lyric documentation wherein the African-American sings their own version of historical events – social, cultural and religious – and forgotten and/or erased narratives are reinstated.

Whereas Jess’s first collection leadbelly adheres rigorously to the imagined personal testimony of the titular blues legend, Olio seeks to complicate the notion that historic restoration can be achieved through single-voiced narratives. This new collection makes, for example, conversations between slave owners and his liberated characters through contrapuntal poems, which can be read in multiple ways encouraging different viewpoints.

He introduces these multiple-voiced dialogues through a rigorous experimentation: with traditional forms like the sonnet, as well as the seemingly hodgepodge layout of the poems, and by encouraging the reader to physically interact with the text by tearing out serrated pages to contort poems and create plural readings.

Olio draws on the part of the minstrel show that later became the Vaudeville as the collection’s organising principle. The Vaudeville followed the main act, providing a showcase platform for various performers. A cast list at the beginning of Olio presents names and short biographies to introduce performers, musicians and artists from 1816 onwards, from the conjoined McKoy twins to Henry “Box” Brown, Scott Joplain, Sissieretta Jones and a plethora of other characters.

With the ingenuity of a musician he scores these characters onto the page. Millie and Christine McKoy (who performed in freak shows throughout the USA and Europe) speak within syncopated sonnets, shaped like butterflies, which can be read horizontally or diagonally. Jess challenges the constriction of the sonnet as a single argument followed by a volta by enabling polymorphic arguments and resolutions. ‘We have mended two songs into one dark skin’ (says the right wing of the butterfly), ‘we ride the wake of each other’s rhythm’ (says the left).

Olio argues that intertextuality is part of any poetic repositioning of African-American history and demonstrates this proficiently by re-contextualising writings by Mark Twain and John Berryman. In Berryman’s Dream Songs Henry, a ‘fictionalised character’, appears as both himself and Mr Bones, and their representations borrow heavily from minstrelsy’s blackfce, black songs and dialect. The African-American poet Kevin Young (in his essay ‘On Form, for the American Poetry Society’) argued that Berryman’s ‘use of “black dialect” is frustrating and even offensive at times […] and deserves examination at length’. Jess’s revisionism arguably responds to Young’s critique by empowering a re-imagining of selected poems from Dream Songs in his poetry sequence subtitled Narratives of the life of Henry Box, in which the runaway slave Henry Box Brown asserts his reality by emancipating his voice from Berryman’s blackfaced ventriloquism. ‘Freedsong: Dream Dawn’ (below) responds to ‘From Dream Song 29’.

There sat down, hard, a thing upon Henry’s heart

so heavy, if he had a hundred years

& more, & weeping, sleepless, in all that time

Henry would not make good

Starts again always in Henry’s fears

a brittle loss somewhere. His old love, his wife.

Stichomythic lines also facilitate conversations between characters across segregated barriers, time and literature, that utilise newspaper reports, excerpts from texts, song lyric and imagined exchanges. Here, Irving Berlin responds to accusations of theft and Scott Joplin replies in the poem ‘Berlin V. Joplin’:

The disparate poems in Olio are held together by a corona of sonnets. Each sonnet is sandwiched between a litany of named black churches destroyed between 1822 and 2015 beginning with MOTHER EMMANUEL AME CHURCH, CS, 1822. The sonnets sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers act as hymn and Greek Chorus. The lyric emancipates by breaking open language spaces (book, poems, testimony, dialogue) producing notes and narratives that ‘burst loose from bondage’.

Olio is a groundbreaking book for African-American historic poetry and American poetry as a whole.