Walking in the Shadows, Standing in the Light

Benjaming J. Larner interviews Imtiaz Dharker

Benjamin J. Larner

Imtiaz Dharker grew up a ‘Muslim Calvinist’ in a Lahori household in Glasgow, was adopted by India, and married into Wales. She is an accomplished artist and video filmmaker, and is the author of eight poetry collections, including The terrorist at my table (2006), and Over the Moon (2014), which was shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award. She received a Cholmondeley Award from the Society of Authors and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Her poems are on the British GCSE and A Level English syllabus, and she reads with other poets at Poetry Live! events all over the country to more than 35,000 students a year. In 2020, she was appointed Chancellor of Newcastle University. Following the publication of her most recent collection, Shadow Reader (2024), which was a Poetry Book Society Special Commendation, poet Benjamin J Larner spoke with Dharker about the relationship between words and images in her work, and casting new light on historical narratives.

Benjamin J. Larner: The collection starts with a prophecy of your death. Without getting too Heideggerian about it, temporality seems to be a great preoccupation in this collection, which abounds with acts of interpreting pasts so as to project (or prophesy?) futures which collapse into presents. For example, in ‘I Am Not Alone’:

shadow draws a map of the journey it has made, hauling the weight of the world through the long light of morning.

How does the experience – or rather, the interpretation – of time relate to your poetics of prophecy, especially given the postcolonial nature of the collection?

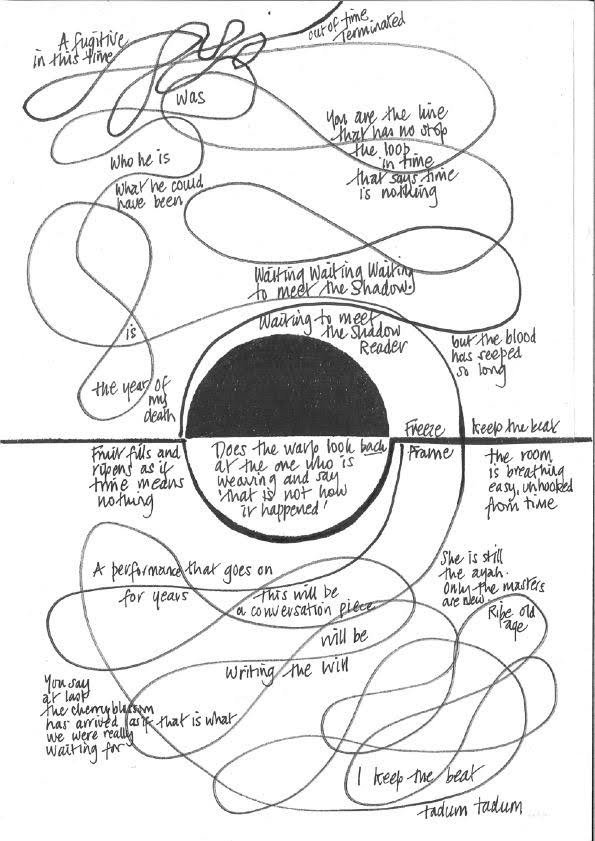

Imtiaz Dharker: I’ve always thought of time as a moving loop, a swooping voracious thing, certainly not a direct line to an end. The best way of saying what I mean is to show you the diagram below. I rely on maps to tell me what I mean and where I am going, and when I start to put poems together, I have to make a drawing to understand how they will move through the frame of the book.

We are all on a trajectory to an inevitable end but, on the way, there are meetings and messages of different kinds, from people trying to connect in any way they can across time and time zones. All the way through the collection, questions arise about who belongs in a given space, who owns it, who is occupying it. Past and future images lie over each other in a double exposure. The future reader’s shadow lies on the page with mine as I write. The Shadow Reader’s prophecy of the year of my death looms across a lifetime but it seems absurd that he has a scroll for my life and not for the ant climbing the stairs with me to the same door.

To briefly clarify who the Shadow Reader is: when I was twenty-five, I was taken, unwillingly, to see a great many astrologers. One was a Shadow Reader who measured my shadow, made calculations in a squared jotter, picked an ancient scroll from a shelf behind him and read my future. I didn’t believe a word of his prediction but even the mind of a non-believer can be possessed, occupied. He said I would live to a great old age and told me the year of my death. That was last year.

Just as the past, present, and future feed into each other, the poems also refer backwards and forwards, with repeated lines, words, or images. They ‘keep time’ with each other through the collection, circling back on themselves. But time is marked here by many voices, few of them mine, foretelling, and retelling through paintings, sculpture, or news reports, saying what has happened or what is about to happen. Many of these voices use various forms of art or artifice for their own ends. Some are self-serving, deluded, or lying outright.

BJL: The collection seems rooted in a nuanced distinction between acts of ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’. To what extent is this derived from your practice as a visual artist and filmmaker?

ID: Working with film does make me pay close attention, framing the action. I want to record details like the driver’s slight movement in ‘For the Minicab Driver Who Looked as if He Needed Feeding’: ‘He looks back for one second / and his face is a passport / and his back is a flag’. Or the fruit flies that ‘rise politely off a feast of black / banana skin to welcome me home’ (‘The Host’). Or ‘the Girl on the Elizabeth Line’ – noticing the way:

he steers you out with the flat of his hand on your back and the people in the carriage try not to look at each other.

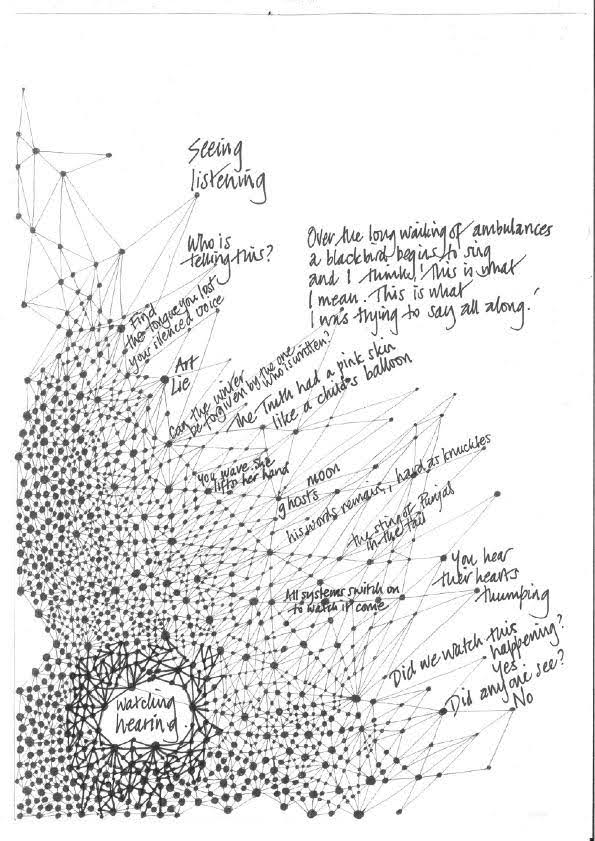

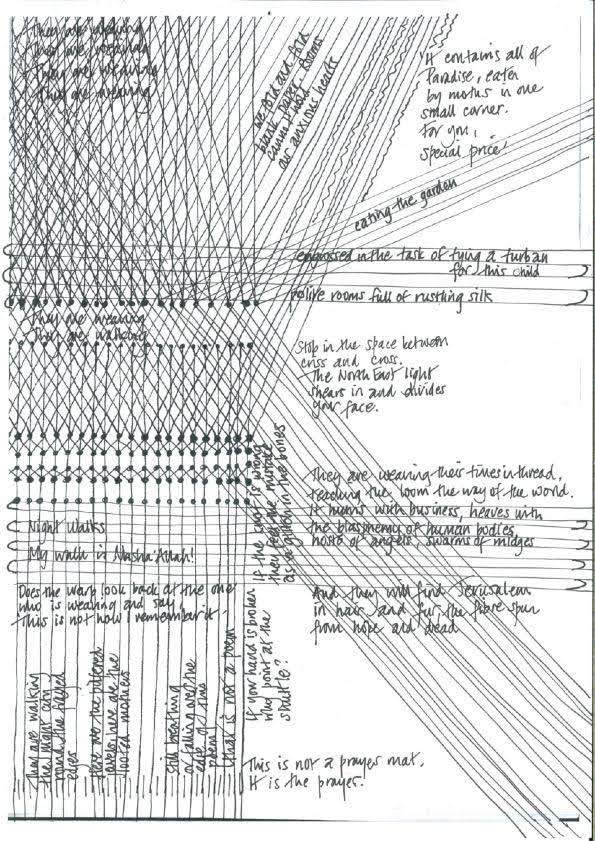

When I go out, I carry loose leaf A4 paper and an isograph pen with black waterproof ink, because when I start a line on a page I don’t know if it will become a drawing or a poem. Through the book, images appear and reappear in different forms. The paradise garden is rewoven as a carpet or a prayer mat or a prayer. It is bartered, frayed, eaten away by insects. It is rewoven by many feet walking, the movement of people a kind of weaving across the face of the earth. Around us and beneath our feet, the insects have lives that glow as brightly as ours. Shadows are everywhere but so are the sightings of angels.

It is true that I think in images and they slide over into words, but I don’t see the two as distinct from one another. They breathe into each other and, I hope, extend each other. If there is a borderline it is porous. But we are all ‘film makers’ now, all watchers with cameras. We have instant access to the record button and are all too ready to switch on for every event, to see ourselves as ‘witness’. In Shadow Reader, cameras on drones record vast global events, the movement of thousands of people leaving the city as it locks down, but Bunny-Auntie is also sharing photoshopped selfies online, and millions are posting pictures of their poolside strawberry mojitos.

The way we relay information, and the way information is delivered to us, can create willing and passive watchers, masters of the mouse, rushing to easy judgements and conclusions. Seeing, on the other hand, is an act of respect towards the one being seen. It creates an opening by paying close attention. Refusing to see can be a kind of wilful betrayal:

did we watch this happening? yes did anyone see? no (‘The map of this country is made of scars’)

BJL: Following on from the above, a poetics of (re)interpretation also seems essential to this collection, being perhaps most overt in the various ekphrastic poems (e.g. ‘The Show’, ‘Boy with a Turban’, ‘Demons Rule’) which beautifully reframe colonial-era visual art. What does the concept of (re)interpretation mean to you as a poet and visual artist? Postcolonialism signals the possibility of overcoming colonialism, yet new forms of domination or subordination can come in the wake of such changes, including new forms of global empire. Postcolonialism should not be confused with the claim that the world we live in now is actually devoid of colonialism.

ID: So much of the art and literature and film we see is made from the point of view of the coloniser, the occupier. I use these poems to talk back. ‘The Show’ looks at a 1786 painting, a puff piece of portraiture by Johann Zoffany, Colonel Blair and his Family and an Indian Ayah. The poem becomes an act of reparation for the ‘Ayah’ who is not an ayah at all but a small child. Even this attempt at redressal is subverted, because in the continuing colonisation by wealth and stealth, she is ‘still the ayah, only the masters / are new’ (‘Did anyone say what happened to the girl?’). In ‘Boy with a Turban’, Queen Victoria’s watercolour sketch of the sixteen-year-old Maharajah Duleep Singh ‘rinses a world away behind his back’. In ‘Fly’, based on The Decapitation in the Padshanama, ‘the bodies interlock / in the dance that happens after war, / war remade in art’. That feeds forward to ‘The map of this country is made of scars’ and how information about conflict is ‘remade’ even as we watch civilians being killed in real time.

All this is tied to the occupation of countries and the violence at the core of colonisation. But as you say, new faces of colonialism, new forms of domination and exclusion rise up. The reporting of events and conflicts in the media is dictated by those who have taken possession of the story and who have the means to tell it. History can be distorted, textbooks rewritten. This is violence of a different kind. In the poems, it slides over into our occupation of the earth, the way we are consuming the earth, eating up its resources; the way we assume we are masters of the world and better than the animals and insects who share the space with us.

BJL: You write the following in ‘Witness’:

Sometimes the truth is not a beacon but a small flame or only the light of a phone falling on the face of a witness.

To what extent do you regard the collection’s poetics of (re)interpretation as one of witness, and is such a poetics ultimately of a personal or a political nature?

ID: Mine is less a poetry of witness than poetry that explores how we witness. That brings us back to ‘watching’ and watching out – how we receive the images, advice, reports, accounts; whether we are to trust the teller or the seller or the maker of the content, or the many voices that speak here. The truth-weaver is a sharp salesman in the bazaar, selling a dodgy carpet: ‘It contains all of Paradise, / eaten by moths in one small corner. // For you, special price’ (‘The Weaver Makes a Pitch’). The question that runs through the collection is: who is saying this, and what are they selling, what is their game? We all know that even in families, when it comes to histories or telling of events, recollections may differ. This is at a personal level, but it is also political. The air we breathe, the water we drink, the bodies we inhabit, the words we write, every act happens in a political context.

In ‘Pink’:

They came along one day and planted a flag on the cheek of the earth. Here is the Truth, they said, And we own it. The Truth had a pink skin like a child’s balloon at a birthday party and everyone had to sing Happy Birthday and God Save the King.

All the tellers in Shadow Reader need to be viewed with caution. This includes the artist, the maker, the writer, even the ‘I’ of the poems.

Can the writer be forgiven by the one who is written? Does the warp look back at the one who is weaving and say, This is not how I remember it, not how it happened at all? (‘Face to face’)

BJL: The collection contains a variety of forms and devices. For example, ‘Where you Belong’ employs the ancient rhetorical device of anaphora, whereas ‘Fold’ and other poems in the collection employ couplets, a staple of English-language poetry. What role does poetic form play in this collection?

ID: I saw the whole collection as a weaving together of different threads, some homespun, some shimmering, and that allowed me to play with any form I wanted for each individual poem. The Shadow Reader recurs and I saw the poems in which he does as slanted, stair-climbing, looking askance at his questionable prophecy. The lines are skewed on the page to reflect the absurdity of the situation. Elsewhere, lines and phrases return as a shuttle does, in a repeating pattern. Sometimes the pattern is broken with a squib of haiku or a Punjabi proverb or a tweet. Through it all, there are unruly voices that insist on adopting their own form and register. Nothing belongs to the supposed maker.

BJL: The collection ends with the poem ‘I Walk in the Shadow’. This poem sums up so many of the collection’s concerns: prophecy, history, art, culture, forms of truth, personal vs mass experience, time, etc. Employing couplets and referencing traditional forms and techniques, such as the sonnet and iambic pentameter (which foundational figures like Howard and Wyatt so firmly established as the ‘natural’ measure of speech in English poetry), the poem literally skews across the page, wiggling out of its bind to its canon-defying, life-affirming end in Arabic (‘Ma Sha Allah’ – God has willed it). Even the title inheres the kind of looking/seeing distinction and lens of (re)interpretation embedded in the broader poetics of the collection: I walk in shadow being readable as walking within the shadow (as in being oppressed or haunted by it), or walking on the shadow (as in stamping on it, taking control over it). To what extent do you regard this process of constantly re-examining history and culture as essential to the vitality of poetry and art in general, a resounding Fuck you! to the Shadow Reader?

ID: These are strident times and it is easy for nuances to be lost in the noise of devalued words. Writing these poems, I was thinking about the weight and power of the words we say to each other, how we greet a stranger, how we draw a map of the heart in the language we use, and how poetry can walk across borders without a passport. The sounds the poems make come from a Mumbai street, the echo of a Shakespearian sonnet, a conversation in a station bar. They come from the language of day-labourers, songs sung by people working in fields, words spoken between lovers, in holy books and unholy curses.

Living and walking on the earth is in itself an act of re-examining history. Writing the poems is a way to take it back and own it. To work, the poems have to be involved with the world, not afraid of getting their hands dirty. I eavesdrop shamelessly in cafés and stations, on trains, on the street. I see it as part of my job to listen to the words around me, not just what people say, but how they say it, the spaces between the words, the hesitations, the accents and odd usages. I suppose there is a furtive element to it, lying in wait for things people don’t even know they are hiding or aren’t ready to tell.

If I shift between forms, it is only to reflect the variousness of the world and fit the many voices. Before I let the poems go out of my hands, I read them aloud to hear if the music is right.

The title of ‘I Walk in the Shadow’ refers obliquely to Psalm 23, ‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil’. Also at the back of my mind were Rilke’s lines from Das Stunden-Buch (Book of Hours: Love Poems to God): ‘Hinter den Dingen wachse als Brand, / dass ihre Schatten, ausgespannt, / immer mich ganz bedecken’ (‘Flare up like flame / and make big shadows I can move in’).

Benjamin J Larner is a disabled poet of Iraqi/Irish/Ashkenazi heritage. He was runner-up in the 2024 Ivan Juritz Prize and was longlisted for the 2024 London Magazine Poetry Prize and the 2023 Dreich Classics Chapbook Prize. Publications in which his work appears include Agenda, Goldfish, Tears in the Fence, A Thin Slice of Anxiety, and Dreich.