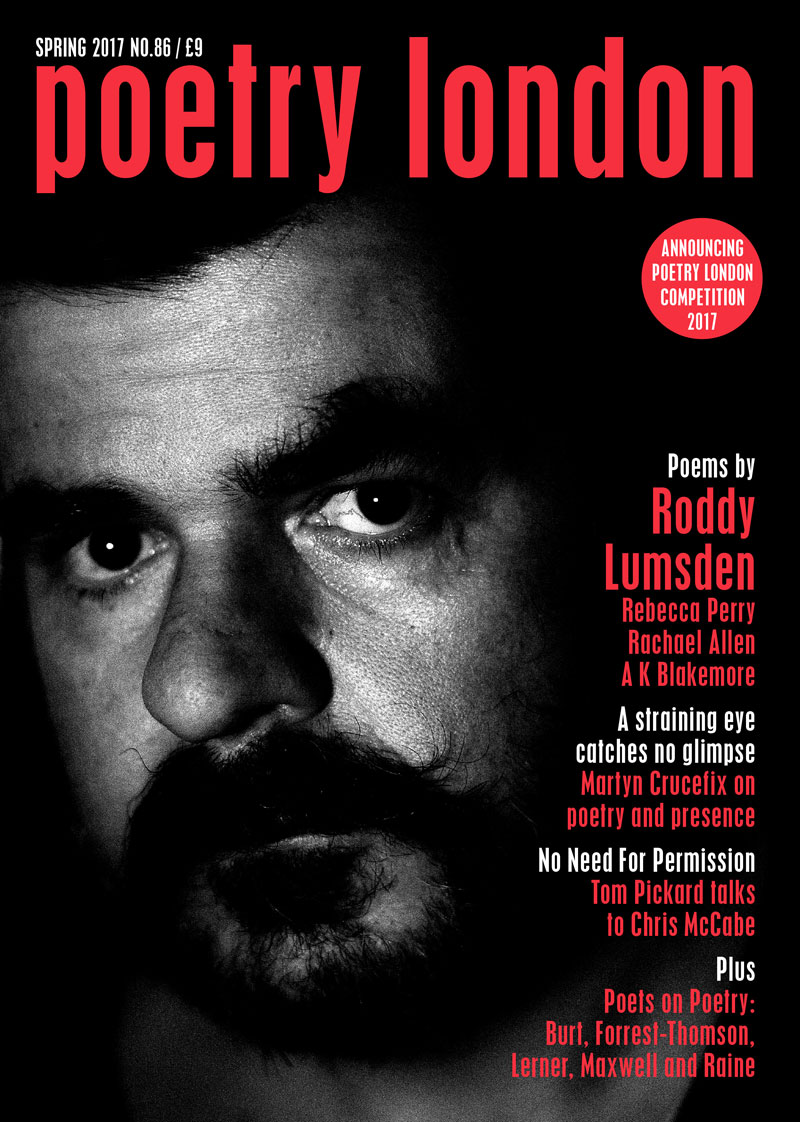

No Need For Permission: Tom Pickard talks to Chris McCabe about poetry and political activism

Tom Pickard meets me at Maryport Station, Cumbria, and drives me back to his home, an old weathered terrace on a street between two pubs. On the wall behind us is a large framed photograph of the young Pickard, face-to-face with his friend Allen Ginsberg. We talk for two hours, breaking off for lunch halfway through. There is a massive collection of books in the room, from Naked Lunch to Paradise Lost, though Tom works up at the top of the house where most of the publications, including his own, are kept. It is nearly fifty years since Tom Pickard’s first collection High on the Walls and his dozen books have recently been gathered by Carcanet as a Collected under the title hoyoot – a word that comes from Geordie slang and means ‘to make redundant’, ‘to throw out’ and ‘to throw money from a wedding car’. Earlier this year his collection, Winter Migrants, was also published by Carcanet. Despite writing with great attentiveness and inventiveness about the British landscape for decades his work since 2002 has been published in America by Flood Editions.

CM: As I’m interviewing you for Poetry London I’m wondering what your relationship with London has been like. Has the city been a source of inspiration?

TP: I’m not sure it’s been a source of inspiration but a source of work and of pleasure too. Although, while on the Wapping picket line opposing Murdoch, I was inspired by the best piece of street poetry that I’ve ever heard, when an old cockney printer shouted at a scab ‘you’re so low you could walk under a snake, wearing a top ‘at’. I joined the North East’s greatest growth industry in 1973 which was the drift south, as there wasn’t any work in Newcastle of any kind. So I left and went to London and dossed on mates’ floors. A lot of Geordies were doing that as a way into London. I always had a lot of friends there and I got to know it really well and liked it. Eric Mottram was always an important figure and influence and he was very much a London man. Tom Raworth, who I think was in London at the time, Allen Fisher, Bob Cobbing and Bill Griffiths. I was also involved with Fulcrum, Stuart and Deidre Montgomery’s press, which published my first book, High on the Walls, and they were publishing Basil [Bunting] so I had those connections. Also with Barry Miles who was running Indica and later set-up the International Times, and I was there for the Dialectics of Liberation, which brought together lots of interesting counter-culture figures. I was also part of a band from Newcastle, which moved to London in the late sixties. We were performing on stage at Middle Earth, in Covent Garden, when it was raided by the Met. The biggest police raid on a club in Met history, I believe. The band fell apart because my kids were back in Newcastle and a couple of the members were hospitalized with jaundice from using smack with shared needles.

CM: Did you feel that what you’d achieved with the reading series at Morden Tower and the Ultima Thule Bookshop, had parallels with what was happening in London in the sixties, for example Cobbings’s Better Books? Was it an attempt to create a similar kind of energy?

TP: No, not at all. Connie [Tom’s wife at the time] and I had been to Edinburgh, we’d run away there together as she was married and we went to the Edinburgh Festival, this must have been around 1962. John Calder had set up a writers’ conference, which had Burroughs, Mailer, Mary McCarthy, McDiarmid and all kinds of writers. We visited Jim Haynes’s Paperback Bookshop and thought it would be great to set up something similar in Newcastle, where you could get hold of work that wasn’t otherwise available. The bookshops were pretty much standard fare in Newcastle at the time, student textbooks – nothing adventurous – just flavour of the month stuff. So the initial influence was from the north, from Edinburgh, and it was only later that I thought of going to London and met people like Stuart Montgomery. Of course London’s bigger, has more money, possibly more energy; but we’d already set up Morden Tower in 1963 – I don’t think London had any impact at that time, we didn’t look to it for permission or inspiration.

CM: Was setting up Morden Tower and the bookshop related to a sense of political activism? Did you see your role in the counterculture as coming first and poetry as being the vehicle for getting those urgent messages across?

TP: They were both together, in parallel. From the age of fifteen and sixteen I was going to demonstrations, so I was engaged with political activism before starting Modern Tower. When I left school they had to open new dole offices, Youth Employment Bureaus, to cope with the massive numbers of ‘bulge babies’ coming onto the job market. With my first typewriter I made leaflets to give out on the dole line, trying to form an unemployed union with the other teddyboys. Ever since I was a child I’d been interested in poetry, the two just came naturally together. In the north-east there’s a tradition of political poetry, they’re not separate – for example in the miner’s ballads and other folk songs – poetry was imbued in the political struggle or was never far from it; check out Tommy Armstrong. The Chopwell miners banner, dating from the Twenties, has Walt Whitman’s line, ‘We take up the task eternal, the burden, and the lesson, Pioneers! O pioneers!’. This was a tradition that I felt a part of.

My first publication was in Anarchy, the magazine. It was about teenagers and what it felt like to be on the dole. We were selling anarchist publications, leftist publications, also Wilhelm Reich (author of The Mass Psychology of Fascism and The Sexual Revolution) all kinds of stapled-together publications with ‘avant-garde writing’. So that’s how it began. By this time I’d met Bunting and he was the next person to read at the Tower [after Pete Brown]. It just started rolling. It became, as well as a bookshop, a centre for the distribution and availability of counterculture material and also a place where people just hung out. But I don’t see my poetry as ‘messages’.

CM: You met Basil Bunting at this time, which perhaps introduced you to modernism including the Objectivists, and had access to his personal library. How did this sit with the very contemporary countercultural activity that you’d begun?

TP: Basil looked like an old flight lieutenant, or whatever it was he’d been in the war. He wore thick glasses and spoke with a posh voice and lived out in an expensive village on the Tyne. I took along with me all of these leftist ideas which he was sympathetic to, or questioned, and I couldn’t have met a better mentor. He was very much a person of the times – Briggflatts really is a poem of the sixties. What we brought to him was an audience, a willing, interested audience. He wasn’t quite a libertine but he was a lifelong socialist and anti-fascist. I remember being in our flat in Newcastle and we passed a spliff around and Basil cupped it in his hands and created a kind of chamber to inhale with and I was thinking, that’s impressive! Then he told me this story where he’d been smoking opium with the Chief of Police in Tehran. He was imbued with that Persian, Middle Eastern culture – he wasn’t an uptight, English gentleman at all, quite the opposite. He became a mentor and introduced me to the Objectivist poets, and that sharpened my tools really. When I got arrested for reading in Newcastle city centre during the first Newcastle festival in 1971 for which I got banned (and still am, as far as I can see) he wrote a letter of support signed ‘Wing Commander Bunting’, saying the Chief Constable should be encouraging not arresting Pickard. Basil was enormously supportive – even speaking at my trial in the Old Bailey in 1976.

CM: I read, in the notes to the new Faber Poems of Basil Bunting, where he said he’d rather read any poetry in dialect, or that is spoken, rather than work written in ‘sixth-hand Latin’. Did this idea of the spoken and the colloquial fit in with the Americans who were visiting and the direction in which you were taking your own work?

TP: Once I asked him, ‘Basil, what about form?’ And he said ‘Well, just invent your own’. And I thought: ‘Okay, that’s good!’ And that’s served me ever since. I’m not interested in using classical forms really. I do go with the notion, like Olson, of writing by ear and the musical phrase. I remember interviewing Ginsberg for Warwick University while I was there as a writer in residence and I was doing a series of interviews about writing – to see if it could be useful for students – and Allen told me, when he’d taken his work to him, William Carlos Williams had advised – rather than trying to obey the metronome to fill out a line, just select what’s live and works for the ear and the form will evolve out of that, essentially. That’s what interests me; you never quite know where a poem’s going to go.

CM: What are your memories of the Sparty Lea festival in 1967? I’ve heard various rumours about what happened that weekend. What do you recall?

TP: I’ve seen it portrayed, by Bill Herbert I think, in the book about Barry MacSweeney [Paul Batchelor’s Reading Barry MacSweeney] and he gets it wrong. He suggests it was some kind of competition between Morden Tower and Barry’s festival. It wasn’t; it was a collaborative venture. Barry wanted to have a gathering of poets, whom he admired or worked with, or was interested in, and he could accommodate them in the weekend cottages his grandparents owned. The night before, all the poets came to hear JH Prynne read at the Tower with Norman Nicholson and after the gig everyone drove out to Sparty Lea, (thirty-odd miles away) and it was convivial. We lived about five miles away in an old farm house. The rumours [about violence] are total bollocks. I never saw any violence at all. I’m sure there was conflict and argument and so on but it wasn’t a bloodbath as Barry painted it! However, Jeremy was recording everyone reading their poems, and my son Matthew, who was three or four at the time, must have been a bit noisy and Jeremy said ‘Shut that fuckin kid up’ or something. I thought, well, this is supposed to be a human occasion and that he was being a bit obsessed and precious about the recordings. So I took the hump and we left. I had an old Land Rover at the time and it was parked on an incline and Jeremy’s Morris Oxford was at the bottom. So I put it into gear, shot down the hill, slammed on the brakes and skidded, denting his wing, justifying it with the angry thought, ‘Well if you’re so obsessed with machines!’. He’s a good bloke and I respect him. So I was sorry to have been impulsive and stupid, damaging his car. He wasn’t in it at the time, of course.

CM: What’s your relationship been with the Cambridge School and that condensed approach to language, have you been wary of what some have described as a ‘coterie poetics’?

TP: In terms of the style of poetry – it’s not mine. I strive for simplicity where I can, and the music of it. I just can’t write that kind of stuff and I get bored with myself if I do. It doesn’t always work for me and I also find a lot of it hard to read. But so what? You need everything really and you need people to experiment in every direction or you just end up with the mainstream – or establishment – which is a more accurate term and frankly that tends to be complacent and ultimately boring. That’s where the harmful coteries reside, where you get ‘bloated volumes by toady poets who sit in circles/ blowing prizes up each other’s arseholes with straws’.

CM: I want to ask about the early responses to your own poetry. I’ve got this quote from a reviewer who said that your book The Order of Chance ‘belongs to the public urinal’. Was this kind of review a good sign that you were getting things right?

TP: He did that thing of damning by finding the worst poem in the book (and there are some worthy of a kicking) then ignoring the rest of the fuckin’ stuff. I don’t know what his problem was. I think some reviewers objected to what I represented to them, which was the uppity working class from ‘The North’. The traditional direction for the working classes was to go up through the system, through grammar school, winning scholarships, getting a classical education and then looking back regretfully and complaining about the difficulty of communicating with the people you left behind and getting loaded with prizes on route to ease the transition to assimilation. I never saw that. I took a different direction; not that it was available to me. But it works very well for some poets. So good luck to them… I’m not being judgmental.

CM: You’ve travelled a lot in the past, living in Poland for example. Is that something you could imagine as more difficult for you to do now, post-Brexit?

TP: There was a long period when I wasn’t published in the UK and during that time my books were coming out in America. That suited me because I had my career in America and my private life here. During the seventies I was getting a lot of gigs in Europe and I ended up living in Warsaw, from the mid-seventies right up to martial law. It was a cheap place to live because I could change my Giro from the dole on the black market. I would go there with whatever I could manage to scrape together from selling stuff, doing odd jobs in London then live in Poland for very little money. It was a way of buying time to write; Bunting always told me that the solution to poverty for a writer was to find a cheap place in the world to live. I’m pretty sure Stalinist Poland wasn’t what he had in mind – but I was in love with a Polish girl – and as I say it was cheap; selling dollars on the black market produced a hell of a lot more zloty than the official exchange rate did. I could take my then in-laws for a slap-up meal, wine, vodka and several courses for about a fiver! Back in London I’m on the dole barely scraping by. When I see Polish people coming here now and working I recognize it’s what I did in their country in the seventies. I still have some friends there, some family. But I was hoping that I could end up living in Ireland. My mother’s family originated there, but with Brexit that’s now looking impossible.

CM: You’ve always made clear your leftist position as a poet outside of party politics. Have you ever been a member of the Labour Party and what do you make of Corbyn – is he the next ‘Astronaut of Fuck’ [Tom Pickard poem about the Labour Party called ‘Hidden Agenda’ published in Hoyoot]?

TP: Although I’ve never been a party member I have worked in various ways with the Campaign group in the Labour Party. I remember years ago doing some gigs for John McDonnell in his London constituency and I’ve always found great integrity and genuine commitment with those people, so I do support Corbyn. I don’t care about him as a personality but I do care about the ideas he’s put forward and the enthusiasm he’s engendered. The Labour Party is not a vehicle for revolution; it clearly isn’t, but I support them because they would do the least damage to most people and through them there’s a possibility of levelling out the corruption of privilege. I recently joined the party because I think there is a possibility of putting the brakes on the reactionaries – if the old New Labour stop sabotaging – and anything we can do to halt the brutal savagery of the DWP, for instance, saves lives. There is an urgent need for an organized resistance to the rise of fascism – corporate fascism, Bullingdon bully-boy opportunistic fascism, free-market fascism. Tory totalitarianism. These are rapidly deteriorating and dangerous times and the victims are piling up. Currently a Labour Party led by Corbyn is possibly the best hope we have for a just society.

CM: There’s always been a strand to your writing that works with historic materials, what has been the appeal with this approach to writing?

TP: Along with musicians (watch your pockets) the people whose company I enjoy most are historians. I failed the eleven-plus and went to a secondary modern where I was in the remedial class or the lowest form until I left at fourteen. They didn’t give a fuck. They didn’t give a fuck about anyone. The school, supposed to be the worst in the country, was later closed down. But I’ve always loved historians. I was brought up by my Great Aunt and my Great Uncle – my Great Aunt was born in 1899, of Irish descent (via Scotland) and she was a great story teller. I know it sounds like a cliché but we would sit by the hearth and she would talk about her childhood, about uncles who died in the war or were ‘squashed between the buffers of two shunting trucks’ in an industrial accident. I was always keen to listen and learn. It’s not a blank sheet, you need to understand the history of your place and your past to move forward and change because we’re always under attack. The most useful model for me, in terms of history in poetry, is Charles Reznikoff who worked with found historical documents whilst retaining the legitimacy and authenticity of those materials; making art out of it in a passionate, human statement.

CM: I’d noticed in one of your books that in the Acknowledgements section you’d included first performances as a kind of first publication. It’s interesting how that gives performance and publication an equivalence. Do you have to perform the poem to know if it’s finished?

TP: For a long time I wasn’t getting published in journals but people were good enough to give me gigs so I wanted to acknowledge them, especially if a poem got its first outing there. Performance is always important, if I can’t perform it, or I can’t make it sing, or there’s no melodic resonance, or it’s clunky – it doesn’t work for me. During composition I have to perform it over and over again until the phrasing is right in the ear and on the tongue – it has to work as a physical thing. I like Carlos Williams’s idea that a poem is a machine made of words or a piece of sculpture made by the tongue.

CM: These new poems strike me as perhaps the most Imagistic of your poems, especially in terms of their pared-down qualities. Does the rawness of the landscape here have something to do with the form of these poems?

TP: All my creative life I’ve been cutting back to make the work as spare as that landscape. There’s a great pleasure in being able to create something from nothing, or apparently nothing. When snowed-up for six weeks at a time you learn a lot about yourself and your environment. I love that sense of emptiness, like when the tide’s out in an estuary, a world that contains everything and nothing at the same time. I’m happiest working on those very tight, short pieces – to pare back to almost nothing and still remain with something.

CM: How do you capture the work when you’re in the wilderness? In the poems themselves you mentioned using notebooks, cameras, an audio device – do you head out there fully equipped?

TP: I’m a compulsive documenter. In the Fells I would go out with a camera, sometimes a tape recorder, a notebook and a backpack. You have to be prepared for a minus twelve blizzard or for the blazing heat. Because we’re an island you’re getting all this cloud mass, sometimes you’re even in a cloud, or you can see one coming. I’ll take photographs; try to record the wind through the cracks in the dykes or whistling through the rushes. It made me listen and look intensely. A camera helps you focus, it enhances vision, as do binoculars. You can frame something, you can bring it closer. With a sound recorder and earphones you can hear things a distance away and isolate everything else. It enables you to pay a great deal of attention to what’s around you. But essentially, walking seems to engender creative thought and a notebook and pencil works if it’s not too cold to remove your gloves.

CM: What are you working on now?

TP: Fiends Fell, a book for Flood Editions, in Chicago, due in 2017, drawing on the journals I kept when I was living on the Fells; prose and poems. Also I’m writing an autobiography Scribbly Jack: Confessions of a Geordie Dole Poet which will also include a load of conversations I recorded with Allen Ginsberg and other folk. A ‘scribbly jack’ is a Northumbrian name for a yellow hammer, but maybe I should call it The Book Of Jobless.

Tom Pickard’s Winter Migrants (2016) and hoyoot: Collected Poems and Songs (2014) are published by Carcanet. His memoir More Pricks than Prizes (2010) is published by Pressed Wafer.

Chris McCabe’s latest publication is Cenotaph South: Mapping the Lost Poets of Nunhead Cemetery (Penned in the Margins, 2016).