Resurrection Dance

Dzifa Benson on two debut collections that reanimate the long-forgotten past

Dzifa Benson

-

Cane, Corn & Gully

Safiya Kamaria

Out-Spoken • £11.99 -

A Little Resurrection

Selina Nwulu

Bloomsbury • £9.99

Given that dance expression is so integral to Cane, Corn & Gully – Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa’s hallucinatory debut collection – it’s curious to see that in the short essay-poem ‘Preface’, which itself unconventionally occurs on page 19 of the book, the poet is adamant that she won’t be using the word ‘dance’ in the collection because ‘every action/breath is a part of the grand / choreograph.’ This might initially seem precious to non-African (by ‘African’ I mean the wider African diaspora) readers, but it’s not entirely surprising to an African sensibility of dance. Most African languages tend not to have a single word denoting ‘dance’ – or ‘music’ for that matter – just for the different forms it takes. It’s not a great leap then to imagine that this has carried over with Africans in regions like Barbados.

There are other ways to parse Cane, Corn & Gully. In the wake of publication, Kinshasa posted a series of tweets that are worth quoting extensively because they are instructive to the book’s intentionality, including the use of labanotation, a graphic system of notating dance movement. The use of it provides a greater comprehension for the reader, and because it’s so important to the raison d’être of the collection, the possibility of embodying some of the labanotation offers a way to kinaesthetically experience the poems too. In a Twitter thread posted on 8 March 2023, Kinshasa writes:

every time I write a poem […] I take into account culture, syntax, breath, various elements of the poem & lived experiences of the performer. […] I managed to revive movements documented by colonialists. […] When I traced these dances throughout history I wanted to put them all in the same physical space because when we dance in the Black diaspora we are always referencing our past.

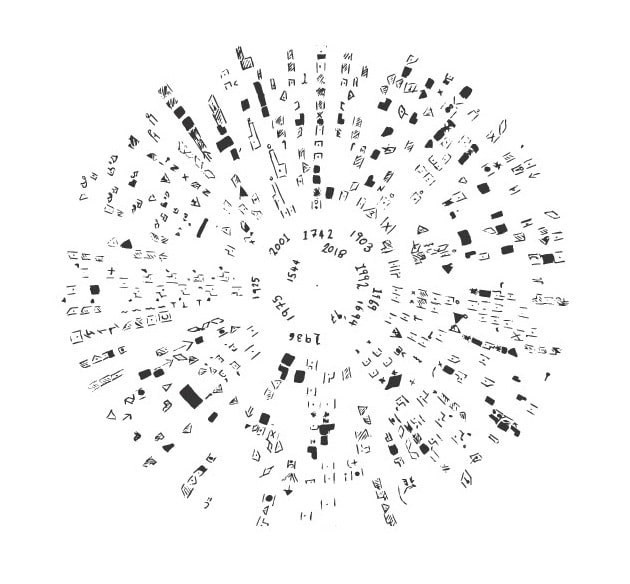

Kinshasa’s method for depicting these dances is what she calls ‘The Barbadian Wheel’:

a way to document Afro-diasporic dances across time and space which can also be used to write poetry. […] This one graphic contains over 1000 dances and every dance is a dance performed by a descendant of an enslaved person.

The Barbadian Wheel – comprised of about a dozen concentric circles of labanotation, surrounding text of several years dating from 1544 to the present – was used to create ‘She, My Nation’, the penultimate poem, which is also the longest in the book. In this poem, all the Barbadian women who were historically silenced and have vociferous, defiant, and earthy utterances in the preceding poems, come together in a grand choreography of movement through a polyphonic medium of words. These words are sometimes juxtaposed against quotations from books written by Europeans, aka ‘Key Informants & Agitators’, who documented their centuries-long colonisation of Barbados. The women are dancehall queens, mothers, prisoners, prostitutes, slaves, avengers of patriarchal violence, and women who express themselves through movement despite iron muzzles clamped around their mouths; their voices resound across the centuries in a non-linear timeline that collapses the gap between history and modernity.

In ‘Excerpt from A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes’, a poem emulating the style of the 1657 Richard Ligon book, ‘these negro women’ ‘cackle with their pelvises’. In ‘The Devil Can’t Two-Step’, a woman ‘jump-split on his straight nose / crushed it with two million jumpers’ and elsewhere another woman’s ‘vagina is a machete’ (‘De Wind Only Likes Me From de Waist Down’), as a ‘mother gave birth to / every version of Barbados but herself ’ (‘Bridgetown, a Man Who Hangs His Socks in a Shopping Trolley Is Saving Up to Buy His Dead Mother a New Hat So She Can Finally Gain Some Control Over the Sun’). The poem ‘A Mother in Israel’, which honours Sarah Ann Gill, a national hero of Barbados, can be read in the sharpest relief because as Kinshasa tells us ‘there are no statues of women in Barbados.’

Cannily, the words ‘black’ and ‘body’ are also absent from the collection. In place of those loaded signifiers that proliferate in discourses intersecting race and womanhood, Kinshasa utilises ‘phrases’, (conventionally repeated motifs in dance recitals) as well as labanotation other than the Barbadian Wheel, at the beginning of each section. For example:

Phrase 20 Notes: sometimes my hips blink drunk, slurring their words as they sip on a pelvis who grins & dips & gives & gives & gives Or: Phrase 41 Guest Choreographer: The Ship Notes: freestyle is not as free as people think it is, you are still controlled by your environment, try not to think too much. remember to maintain your integrity before you find a safe place to empty a mother’s screams * - ‘falling’ can be ‘rising’. - maintain contractions when turning.

Perhaps writing from the body in this concentrated way while constraining certain words accounts for the animal imagery in almost every poem in the collection? Wood pigeons hop off buses, women escape from the mouths of seagulls or cut their way through snakes, dusk sweeps wild-tooth geckos under its toenails, cheetahs climb from women’s heads and chins split like seahorses in labour among a surfeit of phantasmagoric creaturely cameos. It certainly lends a wildness to the poetry, invoking untrammelled expression to give voice to these erased women.

Kinshasa has said that the Barbadian Wheel contains over a thousand dances and that every circle can also represent a different line in a poem. A circle turned in any direction reveals a dance performed by a member of the diaspora. Creating poetry utilising the Barbadian Wheel and other forms of labanotation in the book is sometimes a boon, sometimes a bane to Kinshasa’s poetry. It’s definitely a thrilling, inventive means of creating extraordinarily startling imagery, but in some poems, this tips over into a frenzy of imagery that doesn’t seem to know where to land or falls off a cliff face of meaning.

For the most part, Kinshasa successfully harnesses the nuance of movement to create engendered imagery. It reaches apotheosis in poems like ‘Gully’ which enacts a stuttering, trapped-in-the-gullet speechifying on the page. It depicts, to striking effect, the ebbing and flowing heat of two bodies dancing intimately in the punctuated but wordless ‘Slow Whine’, and remarkably, the exact same method is used to more sinister effect in ‘I Stood at the Edge of an Eclipse Facing My Captor’.

None of the book’s missteps in control take away from the fact that all the elements in Kinshasa’s poetry add up to a galvanising, electrifying, and innovative way of composing poetry, involving the entire corporeality of the poet and heralding a shot in the arm for the variegation of British poetry. In the process, it’s also a portrait of the history of Barbados, and as such, a de facto British history too, refracted through a subversion of the English language itself.

Next to the brilliant overwhelm of Kinshasa’s febrile diction, the direct, distilled, and crystalline poems in Selina Nwulu’s debut full-length collection A Little Resurrection – most of which are no longer than a page – feel like a welcome palette cleanser. If Kinshasa’s poetry is the literary equivalent of a scotch bonnet chilli then Nwulu’s poetry is a tall glass of nourishing milk to soothe the throat of the mind. Here, we find a quieter but insistently questing voice, interrogating the different stages of familial and romantic grief; the cruelty, ironies, and injustices of deportations invoked by Western immigration policies; black womanhood and its attendant privations, stereotypes, and complications; and the conflicting emotions encompassing shame, pride, joy, religiosity, and romance of a Nigerian-British self in the flux of making and unmaking her cultural personhood. In lots of ways, Nwulu’s poetry refreshes the hoary dictum that the personal is indeed (or should be) political.

A little resurrection. It’s important to take particular note of that qualifying adjective ‘little’ which serves to alert the reader to the fact that here, resurrection is seldom the full-blown Lazarus moment of its namesake in ‘Back from the Dead’. That title is the most probing lens through which to refract the entire collection because its meaning and manifestation become less and less straightforward the deeper a reader gets into the book. Resurrection is, by turns, an idea, an action, a too-little-too-late political about-face, or as the titles of several poems indicate, the concept of resurrection in its myriad forms is cloaked in words like ‘repatriation’. Or ‘resuscitate’, ‘revive’, ‘rewind’, ‘replay’, ‘rebirth’, and ‘reincarnation’. Or stripped bare in a plaintive question like, ‘And what if death is not departure but a return?’ in ‘Questions for Mama Mbu’.

Sometimes the notion of resurrection is a keenly yearned for thing invoked to confer celestial grace to a grieving daughter in the first shock of her father’s death, as it does in the first poem of the collection, ‘Conversations at the Bus Stop: Angel’: ‘Now I leave all my doors open, waiting for my return.’ In the collection’s title poem, where the speaker goes to get her hair plaited among women who ‘need only be known by their first names’, the act of resurrection is painful and ephemeral as it is weaved into a meditation on the wounding complexities that impact the black female body in a country like the United Kingdom:

This is the unspoken kinship of the not-quite-safe- on-this-island, those with bodies made so foreign and ungodly for this country to bear, we do not realise we are running on half breath until we sit down, and then see how the women need only offer the attention of their hands to give us some grace. Call this a little resurrection, the making of a new crown, a few hours to look in the mirror and be beautiful.

This kinship with other black people is tested when the speaker of ‘Keep the Bodies Buried’ has to report a burglary by a black man to the police – ‘The police left me in the kitchen, / a lone silhouette, unsure / what to hope for’, which opposes lines from ‘Cords That Cannot Be Broken’ acknowledging the conflicting duality of racial kinship:

I am forever grateful for the company of black people and our ability to dance surrounded by flames. [...] but what else is blackness but a chorus of both praise and grief in one note?

Elsewhere, the opening couplet of ‘Repatriation IV’ asks: ‘If it isn’t clear in the living / where do the dead belong?’ Here, a type of resurrection occurs when the narrator takes her father’s body from England back to Nigeria for burial – ‘his rest, and this is his return / going back to where he came from.’ But another type of resurrection also occurs in the narrator’s imagination within the same poem: ‘Seeing his coffin gives permission / to witness his life whole and I can see / the boy in the man.’

The concept of resurrection is also adapted to powerfully political effect that holds the reader complicit. The note about ‘Repatriation I’ at the back of the book reads:

Despite never having been to Iraq, Jimmy Aldaoud was deported there from the US, as part of the ongoing ICE deportations of Iraqi communities. With mental health issues and a limited supply of insulin for his diabetes, Jimmy died sixty-three days later and was brought back to be buried in the US.

That précis about the vagaries of US immigration policy ensures that lines in the poem like ‘proving nothing but the game / we’ve become’ and ‘Jimmy, finally an American, great again’ resound in the reader’s mind long after she has finished reading the poem. That implication of the reader happens again in ‘Repatriation III’, a short poem that adds up to so much

more than the sum of its brief ten lines. Ostensibly about the Windrush debacle of recent years, it also adroitly manages to encompass the swathe of British history, dating back more than half a century, that seeded the makings of the deportation scandal.

Nwulu’s poetry is quietly but accumulatively persistent, devastating the reader with deeper meaning in repeated readings.

Dzifa Benson is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work intersects science, art, language, the body and ritual which she explores through poetry, theatre-making, performance, exhibition curation, essays and criticism. She was poet-in-residence curator for Whitstable Biennale 2022 and is a Jerwood Compton Poetry Fellow.