The Odd Couple

The most unexpected, and as it turned out inspiring, book I read last year was Airmail (Bloodaxe, 2013), a collection of letters between the American poet Robert Bly and the Swedish Nobel Laureate, Tomas Tranströmer. There is a similarity in the practice of the two writers. Each focuses on the elemental to some degree and both make use of highly personal, sometimes disturbing imagery. But what is as striking is the contrast between the two in personality and temperament.

Tranströmer, by profession a psychologist and often working with disturbed young people, emerges from the letters as grounded, cautious, rational and tolerant – a master of understatement. Bly, who at the time when the correspondence was initiated was editing a poetry magazine from a Minnesota farm, was an enthusiast and agitator for change. In the late 1960s, Bly was at the head of protests against the Vietnam War, marching on Washington or organizing sit-ins. At the same time Tanströmer was supporting writers behind the Iron Curtain in low-level visits to Prague, Budapest, Riga or Tallin.

What united the two poets was a concern for the detail of their art. Much of the correspondence centres on translation – the different associations or connotations of apparent synonyms, the relationship of sound to sense. In the atmosphere of trust that emerges from this, it is possible for Tranströmer to gently demur from his friend’s interest in astrology (‘We have enough misfortunes threatening us as it is’), or to suggest that the only thing less than admirable about Bly’s anti-war poem ‘The Teeth Mother Naked at Last’ is its title.

The letters are a reminder of the contribution supportive relationships between writers can make to the success of an often solitary art. The theme also emerges in another of last year’s books: Elaine Feinstein’s vividly written autobiography It Goes With the Territory: Memoirs of a Poet (Alma, 2013). Feinstein writes of how in the late 1950s, as a woman and someone of Jewish descent, she felt herself ‘at the edge of the English literary world’, taking ‘a perverse pride in being on that periphery’. From that position she used a temporary opportunity to edit the magazine Cambridge Opinion and a later stint as editor of Prospect to become ‘a conduit… for an American avant-garde… outsiders themselves, but ebullient, unfrightened figures’. Feinstein’s connections with writers as diverse as Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Donald Davie and Ted Hughes not only nurtured her own lean and distinctive style, but helped bring new notes into British poetry.

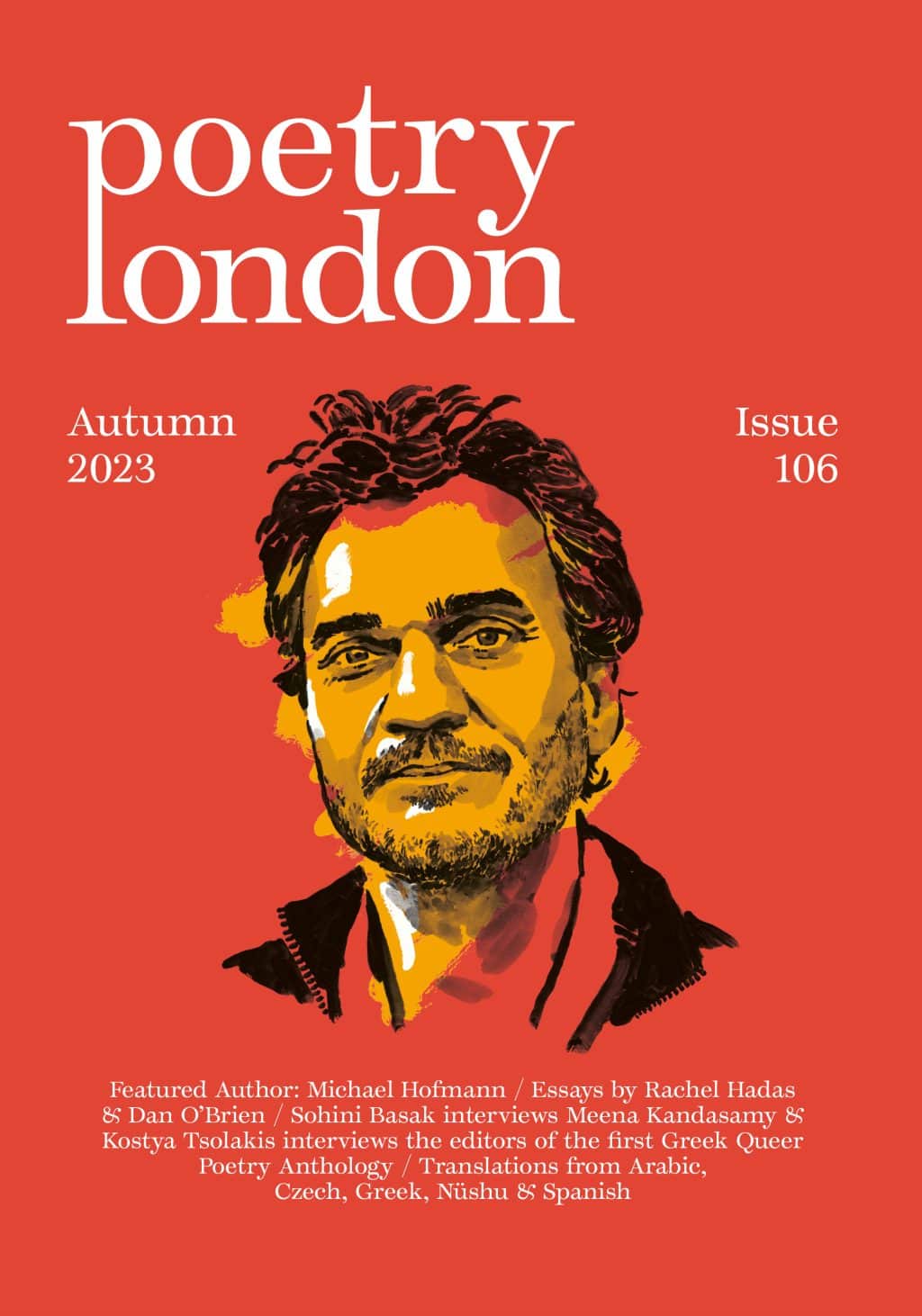

For much of 2013, Martha Kapos and I were occupied with editing The Best of Poetry London, a celebration of this magazine’s first twenty-five years to be published later this year by Carcanet. Among many exhilarating aspects of the task (there were also a few tedious ones), revisiting past issues gave us a picture of the way connections between poets can lead to deeper understandings and greater creative opportunities. The first editors of Poetry London – Moniza Alvi, Leon Cych and Pascale Petit – were poets looking to move outside their own circles and make contact with others of their generation first in their home city and, quite quickly, nationally and internationally. The editors to whom they have passed the baton have continued that vision and also sought greater communication between different generations of poets. This issue of Poetry London represents or responds to work of poets from their twenties to their nineties. Needless to say these poets are various in temperament and experience. Beyond surface differences, what we hope they have in common is energy, imagination, and the passion to shape language with precision and care.